Changing world changing church

Michael Moynagh

- 60 minutes read - 12582 wordsCHAPTER ONE: ONE CLICK FROM EXTINCTION

The Harvard Business Review is not most people’s idea of a light read. But if you had flipped through the pages for July/August 1998, you would have come across an article by American management gurus Joseph Pine and James Gilmour, entitled "Welcome to the experience economy'. In it they argued that the advanced world is racing into a new era.

Consumers have been getting bored. They go to the same old shopping malls, see the same old shops, view the same old brands, and they long for something new, something exciting, something that will arrest their interest. Retailers and manufacturers have developed a new line of business in response, experiences — and consumers love it.

Entertailing

British Airways, for example, is explicitly not in the business of selling journeys. It sells a distinctive experience of travel — one that enables the traveller to take time out from the frenetic pace of everyday life, recuperate, and arrive refreshed and ready to clinch that business deal.

More and more restaurants see their main activity as providing a particular experience of eating rather than selling food. At theme restaurants such as the Hard Rock Cafe, Planet Hollywood and the House of Blues, the food is just a prop for what is known as 'eatertainment'.

In one Los Angeles restaurant I visited, halfway through the meal the waiters and waitresses leapt on the bar and performed a tap dance routine, spinning the plates above their heads. New to this, I watched anxiously, wondering if my food would arrive on the plate or spin across the air! In Britain, Waddington’s recently announced that it is to open a chain of 'Monopoly Cafes'.

Shopping itself is being transformed into an experience, with sights that titillate the eyes, subtle aromas and background music to create the right ambience. American stores such as Niketown, Cabella’s and Recreational Equipment Incorporated draw in consumers by offering fun activities, fascinating displays and promotional events (sometimes dubbed 'shoppertainment').

Here comes the immersive world

Emerging technologies have encouraged whole new genres of experience, such as interactive games, Internet chat rooms and multi-player games, motion-based simulators and virtual reality. They are making it possible for people to become totally immersed in experiences. 'A Bug’s Life' presentation at Disney World, for example, involves all the senses, including smells and creepy-crawly sensations under your legs.

As virtual reality becomes cheaper and more accessible, these experiences will be ever more sophisticated. We are entering not a visual culture (that was ushered in by television), but an immersive one.

Buying transformation

Nine months after their article, Pine and Gilmour published the book. [1] It contained the punch-line of their argument. Writing for a business audience, they asked what type of experiences would be most in demand. Their reply? Life-transforming experiences.

More and more people are seeking experiences that change them in some way — that make them feel better or look better, for example. So they will go to the gym and punish themselves for an hour, to emerge with a glow of achievement. Or they will acquire new skills from gliding to deep-sea diving, to become more interesting people. Or they will holiday abroad and study the culture of their destination to become more informed.

According to Pine and Gilmour, successful businesses will be those that market experiences which change people’s lives.

And of course that is the business the church is in. For the past 2,000 years, far longer than the life of any corporation today, the church has offered people the opportunity to have their lives transformed — by Jesus Christ. As we hurtle into the new millennium, the very thing that our society craves — life transforming experiences — is at the centre of the church’s mission statement. It’s the heart of the gospel, a gospel astonishingly relevant to the experience economy. Could the new century be the church’s century?

Going backwards

Yet as the Seattle-based futurist, Tom Sine reminds us, 'We are going backwards not forwards in global evangelisation. 28% of the world’s people would identify themselves as Protestant, Catholic or Orthodox today. By the year 2010 that will decrease to 27% and continue to decline from there because the global

population is growing more rapidly than the global church.' [2] The trends are especially gloomy in the West — and, despite what some think, that includes the United States.

The vanishing church show in Britain

Church attendance has plummeted in Britain. In 1979 5.4 million people in England attended church on an average Sunday. Ten years later that number had dropped to 4.7 million. Nine years later, in 1998, the total had collapsed to 3.7 million. A 13% decline over ten years was followed by a staggering 22% fall over nine years. [3]

Some people take comfort from attendance at church midweek. Figures for Sunday, they say, exaggerate the speed of decline. More people are going to church on weekdays. But there have always been midweek services. The number switching to weekday church is a tiny drop in the ocean of all churchgoers. It barely dents the vast haemorrhage from Sundays. 'Good news! There are slightly more on the Titanic than we thought [4] is hardly encouraging.

Others claim the figures are not as bad as they seem because people are still committed to church, they just go less often. Sunday attendance is down because more people are going once or twice a month instead of every week. This is part of a bigger picture. Up to the 1960s it was not uncommon for many people to attend church twice on a Sunday. Since then 'two-timers' have almost completely disappeared. Now we are told that once a Sunday is giving way to once every few weeks.

This can scarcely be good news for the church. It suggests that the faithful are becoming less committed. With so many other pressures on people’s time, church is being squeezed out. Will we find that people attend church less and less often, till they stop going altogether?

More hope for Australia?

If the news is bad in Britain, it is not much better in Australia. In 1950 44% of the population attended church once-monthly or more. Today the figure is just 10%, 1.8 million people. There are signs that the nosedive bottomed out in the 1990s, but not that it has gone into reverse.

Indeed, the picture may be rather flattering. Church numbers have been lifted by successive waves of immigration. Many newcomers arrived with Christian backgrounds and have continued to attend ethnically-based churches. As they become more integrated into mainstream society, their children are likely to pick up the non-churchgoing habits of their Australian friends.

Not much comfort for the United States

This seems to be the story behind the continued health of church attendance figures in the United States. Black, Hispanic and Asian congregations are growing at a significant rate. But with the exception of the Catholic Church, virtually all the mainline denominations are in decline. In 1968 eleven mainline Protestant denominations represented 13% of the US population. By 1993 this had spiralled down to 7.8% — a 40% drop. If the present trends continue uninterrupted these churches will be totally out of business by 2032.

Some of this decline is being offset by new churches like The Vineyard, but even growing denominations saw their growth rates slow between 1985 and 1993. The portion of the American population involved in church actually declined over that eight-year period.

Over the past ten years Barna Research reports that while older generation attendance ranged from roughly 40% to 60%, the Buster generation (born between 1965 and 1983) came in at 34%. Even these figures may be optimistic. Kirk Hadaway, chief statistician for the United Church of Christ, has convincing evidence that Americans are over-reporting their attendance. [5]

The 'incredibly shrinking church' in Britain and Australia is set to become a reality in the United States as well. Pockets of growth cannot hide the gradual erosion of church across swathes of the population.

Time for a rethink

There is no time for complacency. Peter Brierley of Christian Research notes that church attendance figures in England are alarming not just because they are declining, but because the rate of decline is speeding up. If the rate of change continues, the percentage of people in England going to church in 2016 would be down to 0.9%! 'Just one generation, and we would indeed have bled to death. [6]

Of course, you cannot project today’s trends into the future unchanged. Lots can happen to make a difference. Trends can get worse! They can also get better, but they won’t get better automatically. Something has to happen to produce the change. What would have to occur to restore the vanishing church not only in Britain, but in other advanced societies?

Church has lost its way

Certainly in Britain, New Zealand and elsewhere there is growing recognition that we cannot go on as we are. Many clergy and lay people know that today’s church is not working, it is not connecting with people any more, but they cannot imagine anything different. They struggle on with tried and trusted methods, feeling uneasy but with little vision for how things could change.

Others are busting a gut to make existing churches grow, sometimes succeeding, but often wearing themselves out — and their congregations! — instead. They hear about 'successful' churches and think, 'If it can work for them, surely the same approach will work for us'. They ignore how different their circumstances are, or how beacon churches often achieve growth by drawing Christians away from smaller churches. What will happen to these 'successful' churches when their small-church feeder-systems dry up? [7]

Still other ministers look back to the 1970s and '80s, desperately hoping to repeat what was effective then. But the world has moved on, and so frequently they are disappointed. They burn out, exhausted and disillusioned because they see so little fruit.

A few leaders are trying fresh forms of church — imaginative experiments which may in time blaze a route to a radically different church that reconnects with the world. These pioneers are responding intuitively to opportunities around them, but sometimes they feel alone and wonder how far their efforts fit into the larger whole.

Finding a new path

This is a book about why the church need not disappear, and how we can lay the foundations of substantial growth. It is a book therefore for those who are committed to church.

Yet for many people church is the last thing they want. They might feel offended to think that we are trying draw them in. If our approach was in any way patronising ('we’ve got the answers, you haven’t'), or at all manipulative ('we’ll make friends with you but only to get you to church'), or lacking respect ('we’re more keen to talk about our faith than to listen to yours'), then our attitude would indeed be offensive.

Our task is not to press people into church. Rather, church is a gift. We can make it more attractive. We can offer it to people. But we must respect each person’s decision as to whether it is a gift for them.

This is a book, then, not about intrusive evangelism, but about how church can be made attractive to those who might want it.

The shape of the book

The book is in two halves. First, we shall look at some epoch-making trends that will shape our society over the next 20 years, and which church leaders — ordained and lay — need to understand if they are to take society by storm.

The template of daily life is changing as we move from standardised society to an it-must-fit-me world. Even more than today, life will be about managing choice. It will be about jumping between consumer and workplace modes of thought, which are very different to each other. How will the church make contact with this emerging world and the tensions within it? Today’s church has become disconnected from people, but it will have huge opportunities to make contact in future.

The second part of the book describes how the church can grow once again. It starts with a vision of the church in 2020 — a church that has become highly responsive to the different fragments of society, and eager to network those fragments together. It describes how this future is today becoming a reality in some of the new forms of church that are being trialled. These experiments could herald a dramatic shift in evangelistic strategy — one that builds new expressions of church for a new era.

This strategy can draw on lessons from society, but it needs to be driven by Scripture. So chapter 10 runs the strategy through a biblical X-ray to confirm that its roots are indeed in Scripture. We then ask how new believers — as part of this strategy — can be helped to become agents of social change.

The book concludes with some practical steps that smaller churches, larger ones and denominational leaders can all take. These steps would replace a 'you come to us' church with one that comes to you. In an it-must-fit-me world, they would create a church that fits — both people and God.

So mission equals evangelism?

Does this mean that evangelism must be an absolute priority for church? Some would say so. Others would claim that the church’s mission is much bigger than that — that the church’s central task is to bring society closer to God’s values. Questions of justice may take priority over evangelism.

Others again would feel more comfortable with the idea that God is active outside the church — that just as he used rulers in the ancient world to achieve his purposes (e.g. Isaiah 45:1) so he continues to work in the world to advance his cause. The church’s central task is not to colonise society for God, but to attend to what God is already doing in the world.

Learning from the future

To sharpen our focus we shall draw heavily on the work of the Tomorrow Project, which has been researching the future of people’s lives in Britain over the next two decades. Backed by companies, charitable trusts and government departments, the Project has examined ten aspects of people’s lives, including "People, faith and values'.

Some 200 experts have been interviewed, including experts outside Britain, and ten two-day consultations have been held involving eminent researchers, policy-makers, practitioners and people from the media — around 20 at each consultation. The initial results were published in May 2000 as Tomorrow, [8] which was distributed to 50,000 key decision-makers and opinion-formers in the public, private and voluntary sectors.

The research has yielded a megabase of societal trends which reflect developments not only in Britain, but in the global economy. Even the UK data has planet-wide significance because much of what is happening in Britain echoes the advanced world as a whole.

If we are to evangelise advanced society, we need a fresh mission strategy — a different framework that can channel our prayers and our initiatives to more fruitful ends. Nothing less than a makeover will equip the church to reach the changing world that is emerging so rapidly before our eyes.

CHAPTER TWO: HELLO, IT-MUST-FIT-ME WORLD

Go into Starbucks, the American coffee house chain now expanding round the world, ask for a cup of coffee and they will think you are mad. 'Excuse me, sir, is that cafe latte, cappuccino or expresso? Do you want the New Guinea Peaberry or the Guatamala something else?' The choice is vast — so great it leaves some people paralysed. Fortunately, they can choose 'coffee of the day'.

Starbucks is so large that it can use its huge size to bulk-buy, at bargain-basement prices, coffees to suit all tastes. It is an example of how the second stage of the consumer revolution is transforming our lives, almost unnoticed.

The new consumerism

The first stage, mass consumption, swept through the United States between the wars and into Europe in the 1950s. Firms used the advantages of size to expand the range of standardised products that people could buy. A large supermarket today may stock 22,000 product lines or more. Once you have selected the product, one item is much the same as another. Apart from differences in size, each packet of Kellogg’s cornflakes is the same.

A glove, not a straitjacket

The second stage of the consumer revolution, mass customisation, began to have an impact in the 1980s. More and more companies are using size to tailor products more closely to the demands of individuals or small groups of customers. One of Britain’s insurance companies, Legal and General, promised, "You can choose the level of cover that suits you.'

Mass customisation is advancing so rapidly that it is about to become the defining feature of our consumer world. Look at a Ford assembly line and you will find that almost every car has the name tag of its future owner. The trims and fittings have been customised to match the preferences of scores of different buyers.

In some of the Levi stores you can go into a booth, have your body measurements taken by laser, the numbers are sent down the wire to a factory miles away, and two or three weeks later a pair of jeans, made to fit your exact body measurements, is delivered to your front door.

Dell Computers web-site links customers directly with the production line. Place an order on the site, it will go straight to production, and you can sit back and wait for the PC to be delivered to your door. No need for people in sales, inventory or retailing. Customers can enter their own specifications and know that their customised PCs will be delivered at rock-bottom prices. The customer becomes a partner in designing the exact computer required. This will become standard for many products. Musicmaker.com, for example, allows you to order a CD with your own selection of tracks on it.

In some ways it feels the way it did before the industrial revolution, when goods were crafted to the client’s exact requirements. The big difference is that this attention to the individual is now being combined with low-cost production secured by the benefits of scale. A vast range of personalised goods can be brought to a wide market.

Collaborative customisers dialogue with each customer to help them choose exactly what they want. So for example at Custom Foot in Westport, Connecticut, a salesperson will take your measurements using a digital foot imager, you will be shown a variety of design elements such as different toes and different heels, you make your choice and the final specifications are dispatched electronically to Italy, where the shoes are custom-made.

Adaptive customisers offer a standard product that is designed for users to alter themselves. Select Comfort of Minneapolis, Minnesota, for instance, designs and manufactures mattresses with air chamber systems that do more than automatically contour to the bodies of those who lie on them: users can adjust the levels of firmness, changing them from night to night if they want and selecting different levels for both sides of the bed.

Cosmetic customisers present a standard product differently to different customers. The product may be packaged specially for each customer, for example, as with the Hertz #1 Club Gold Program. You still get the same basic car, but you bypass the line at the counter. The shuttle bus takes you to a canopied area where you see your own name in lights on a large screen which directs you to the exact location of your car. The car’s boot is open, your name is displayed on the personal agreement hanging from the mirror and where weather and law permits the engine is running, waiting for you.

Transparent customisers give individuals unique goods and services without letting them know explicitly that these products have been customised for them. The Ritz-Carlton for instance observes the preferences guests show during each stay. Do they switch toa classical radio station, select chocolate chip cookies and prefer hypoallergenic pillows? The information is used to tailor the service the customer receives next time they visit. The more often you stay at its hotels, the more the company learns and the more customised goods and services are fitted into its standard rooms. It is hoped that this will make the hotel the guests' preferred choice. [9]

Consuming everything

Consumerism sets the tone for so much of our lives that, not surprisingly, this new stage of the consumer revolution will affect almost every aspect of our existence.

In education, for example, California’s Stanford Research Institute is developing distance-learning packages in which modules will be broken into ten-minute segments. You will be able to do two segments on a train journey, and perhaps one in a taxi ride — learning when and where you want. Keeping this material up to date will be expensive, and so education providers are likely to combine together to reduce overheads. Just-intime education — learning when you want — will be made possible by the advantages of size.

In health, the human genome project is organised internationally. Pharmaceutical companies are rushing to transform its results into a revolutionary new generation of drugs, which will be targeted at the particular genetic make-up of individuals and small groups of patients. In the process the companies are merging to pool research and development. Once again, scale is being used to provide a more individualised approach.

In church the phenomenally successful Alpha course, which boasted over one-and-a-half million participants in the 1990s, offers a ten—week introduction to Christianity. Material is produced centrally and supported by national advertising campaigns. Yet courses are organised by local churches to fit their particular circumstances. The highlight of each one is a day or weekend away, when participants are encouraged to have their own, individual experiences of God. Many report that this was a turning point in their lives.

The new workplace

One certainty about the future is that people won’t spend all week behind computer screens working from home. They may stay home for one or two days a week, but not for the whole time.

That is because the benefits of being together at work are too great — the feeling of being involved, the chance to make friends, the chit-chat by the vending machine which can spark a bright idea, the building of trust by seeing people in different contexts, the protection of confidential information (which organisation allows its treasured secrets into people’s homes?) and managing stress, which is aggravated by isolation and lack of social support. There are huge advantages in being present in a larger work group.

Made-to-measure work

What is changing is how these benefits are becoming tailored to the individual. Sometimes this is happening in small ways. More employers are encouraging staff to dress down, giving individuals more choice over what they wear. Even in factorylike call centres, attempts to personalise work are being tried. In some centres employees have been grouped into small units to give a stronger 'family' feel, while in one or two cases staff have been given much greater control over what they do.

More significant perhaps is the greater discretion being offered to some employees over when, where and how they work. Some organisations are allowing staff more choice over when to work at home and in the office, and whether to work through the day or — from time to time — in the afternoon and evening.

In London a 'Timecare' computer programme has been set up for nurses. It allocates shifts according to when nurses are most in demand and when they want to work. Nurses' requests for time off are logged on a computer, which keeps a record of the hours they have worked. If someone would prefer to work for five hours but has to work for eight, the three extra hours are banked with the computer and added to time off later. The more surplus hours a nurse banks, the more favourably will the computer treat requests for time off. Nurses have more flexibility in choosing which shifts to work. [10]

Employed to be self-employed

Payment-by-results is spreading, with performance-linked bonuses a larger component of many people’s income. More jobs are being franchised — such as counter operations within retailers. These developments herald a significant trend. Most people will still work for a single organisation, but their work will feel more like self-employment. People will be paid for the tasks they perform rather than the hours they actually work

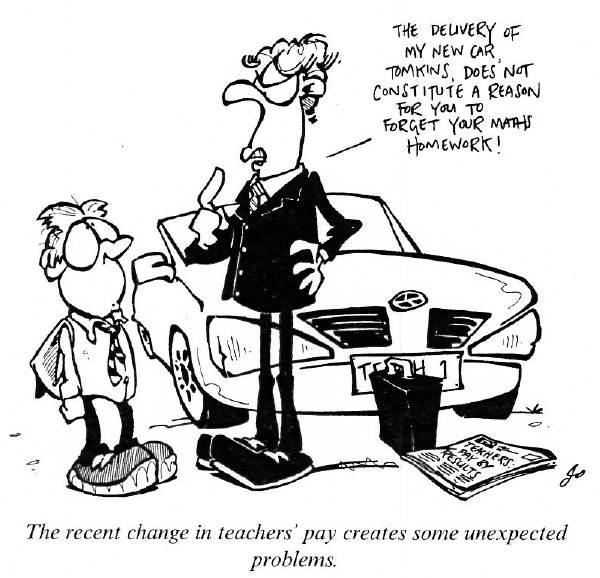

Teachers for example may contract to achieve certain test and exam results. Targets would be set according to what could be reasonably expected of pupils in the particular school. Teachers would agree to teach so many pupils and secure a standard set of results. Those who beat the target would get a bonus, while those who under-performed would be paid less. Teachers would be paid for a task, just as a self-employed plumber might be hired for a particular job, rather than for the time they put in. The spread of, performance-related pay in many schools may be a first step towards this.

Personal assistants may be hired to perform specified assignments. How they organise those tasks, when they are in the office and when they work from home, and the hours they actually work would be up to them, so long as the tasks were performed to their boss’s satisfaction. They would be responsible for managing their own work, as if they were self-employed.

We are moving from mass production where workers were treated in a standardised way to the 'individualised organisation', where employees are given more opportunity to be themselves and to manage their own work. The benefits of working in a larger group are combined with greater personal freedom.

Leaner, meaner and faster than ever

A similar pattern lies behind the spread of 'networked organisations'. In recent years organisations have been breaking down into smaller components, with each unit having greater independence.

This will continue. Sometimes this will be through more outsourcing — buying in services instead of supplying them in-house — which allows organisations to focus on what they do best. Sometimes it will be through decentralisation to give individual units greater discretion. The different elements of an organisation end up with more freedom to specialise, to develop their own strategies and to respond quickly to the market.

At the same time networking will continue to make available the benefits of size. Separate firms may work together to share research and development costs. An entire supply chain may operate as a single unit, exchanging information and working collaboratively to secure just-in-time delivery, raise quality and gain other efficiencies. Potential competitors may cooperate in dividing up the market, to guarantee each company a larger share.

Companies will collaborate so that buying an airline ticket on the Internet, for example, will become a gateway to other services. When you get your ticket, you will not only buy insurance as now, but other services such as a hotel reservation, advice on quality restaurants and a theatre ticket in the city of destination. This is already beginning to happen, and we shall see plenty more examples. Cooperation makes what each organisation has to offer more attractive.

The emerging 'network society' combines the advantages of scale through collaboration with more freedom for organisations to play to their strengths. It is a trend that is affecting every sphere — the public, private and voluntary sectors, not to mention the media. There is no future in going it alone: you can do more to achieve your goals if you work with others.

Churches who often struggle to work together have much to learn. As we shall see, cooperation will be vital if church is to connect with the emerging world.

www.newgovernment.gov

Mass consumption and mass production were accompanied by mass government. The government treated people in a standardised way — the rules for one person were the same for everyone. No wonder bureaucracy became a dirty word: people wanted to be treated as individuals. But this is beginning to change, and the pace is hotting up.

Customised government

Governments in the advanced world are rapidly transferring their services on-line. Tax returns are just one example. They can now be dispatched on-line and enquiries sent electronically to the tax office. The door is opening to a more individualised relationship with government. People won’t have to wait till office hours, they will be able to communicate electronically with government whenever they want.

It is widely recognised that social exclusion is best tackled by gearing the resources of the community to the varying needs of individuals. In parts of Australia for instance a social worker, paid for by the community, will actually live for a time with a dysfunctional family, helping members to change their patterns of behaviour, before gradually withdrawing — the ultimate in personalising community support.

Down to the local

Likewise, all the main political parties play lip-service to the importance of taking local differences into account when framing policy. Education, employment and health action zones in Britain give expression to this. They are designed to foster local solutions to local problems.

But how can a local focus be combined with the coordination of resources at state or national levels? A national (or state) tax system with uniform rates harnesses the wealth of the better-off to support those in need. It is highly efficient. Imagine the extra costs of myriad local taxes, each with their own bureaucracies! But it also gives great power to central government. Using that power to increase local discretion remains an immense challenge.

This will top the political agenda in the years ahead as government continues to decentralise, especially in Britain. In the UK, devolution of powers to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, a newly elected mayor for London and the possible election of mayors in other cities has begun to reverse the centralisation of government. This process is almost certain to continue, forcing government to become more sensitive to the different priorities of different areas. [11]

The challenge will be to combine the advantages of greater local control with the benefits of doing some things centrally. What is best done centrally and what locally? How local is local — city level or regional? Where is the centre — in the case of Britain, Westminster or Brussels? And how should the different levels of government interact?

In short, how can the benefits of scale be combined with the advantages of customisation?

Perhaps the ultimate in customised government would be a customised Cabinet. Instead of having Cabinet ministers for Education, Health, Social Security and the like, ministers would speak for particular client groups — the elderly, children, the unemployed and so on.

Ministers would order services from existing government departments and bundle them together so that they were suitable for their clients. The Minister for Disabled People for example would order health, education and other services, and ensure that they were designed appropriately.

A far-fetched idea? The UK is taking small steps toward this, with the appointment of Cabinet ministers to champion women and older people, in addition to their existing briefs. Might we see, in time, further steps towards this?

A sea-change

So we are witnessing a major shift in the tectonic plates of society. Everywhere we turn, the same trend is at work. We are moving from an off-the-peg to a tailor-made world.

standardised products, to treat workers in a standardised way, to develop standardised organisations and to deliver standardised government that was roughly the same in every place. In the tailor-made world scale will be used to customise products, to treat workers in a more individualised way, to develop networks in which independent organisations share resources and to deliver government services that will increasingly vary from place to place.

A long journey remains. Many attempts to personalise organisations are clumsy and unconvincing. Call centres for example, in the name of good service, leave consumers pressing one phone button after another. When they eventually speak to an operator, customers scream because their particular question can’t be answered. Genuinely personalised service seems miles away. But as more organisations leave standardisation behind, they will become better skilled in relating to individuals in a personalised way.

How will organisations use these relationships — to serve people or exploit them?

Size with individualism

Two features of our society, then, are coming together. One is the importance of size, reflected for example in company mergers, in organisations which are networking so that they can pool their resources, in global marketing, in the emergence of regional groupings like the European Union, and in the widespread feeling that the world is becoming so big and complex that we can scarcely understand it. 'A big world needs a big bank' claimed a recent UK commercial.

The other is the growing individualisation of society. Values are a matter of personal preference. The individual must be allowed to choose. It’s up to you…

In mass society, size and the individual were often pitted against each other. Workers felt like cogs in a machine. The individual was treated in a uniform way. Today we are crossing a watershed as scale is increasingly used to expand individual choice and to help individuals secure exactly what they want. Size and the individual are working more closely together — at least on the surface. We have entered the age of personalised scale — an it-must-fit-me world.

Tailor-made for post-modernity

A post-modern mindset will be at home in this new world. Though the term 'post-modern' is complex and has sparked much debate, one of its key features is the view that we must not universalise truth, we must not describe the world with one big story, because in doing so we may fail to hear — and even stifle — dissenting views. The 'big story' of male hierarchy, it is said, marginalised the very different stories of women.

This central tenet of the post-modern mindset has a structure which matches that of personalised scale. Whatever postmodernists say, within the post-modern outlook there is a big story. Paradoxically, what that big story says is that there are no big stories. It is a big story which legitimises 'little stories'. It compels us to pay attention to different stories and not to smother them with claims of universal truth. It validates the approach, "You decide'.

In other words, scale — the post-modern big story — is being used to give individuals greater freedom, freedom to have their own views of the world and for these views to be heard. It is a scale serving the person.

Many people think that we are entering 'new times', as radically different to the past as the industrial revolution was to the agricultural world that preceded it. What will these 'new times' look like? Four ways of describing them emphasise four different features.

Knowledge is emphasised by those who think that the information revolution will be central to the new world. Essential to this revolution is knowledge. We shall spend more and more on buying knowledge — from recipe books to TV travel programmes, or on buying products whose value is based on knowledge, such as the service of a fitness instructor. 'The real assets of the modern economy come out of our heads not out of the ground: ideas, knowledge, skills, talent and creativity.

Networks are stressed by those who believe that the communications revolution will be central to the new world. People across the globe are becoming connected in new ways, and this will transform our lives — even more so when we can communicate visually both on-line and by mobile phone. What people crave through the new media is not so much knowledge as fresh opportunities to be in touch with others. New networks will give rise to a new society. See Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, Blackwell, 1996.

Fragmentation perhaps lies at the heart of post-modern perspectives. Shared values that hold society together are giving way to a pluralistic world, in which a variety of beliefs rub shoulders with each other. As global forces lift power further and further away from the individual, people will increasingly identify with their physical neighbourhood, or with an ethnic group or with groups that share a common interest. These will provide meaning, belonging and security in a complex, alien and risky world. Central to this is the rise of the consumer culture with its emphasis on choice. Krishan Kumar, From Post-Industrial to Post-Modern Society, Blackwell, 1995 provides a useful introduction.

Personalised-scale has been a focus of the Tomorrow Project. It owes much to 'Post-Fordist' thinkers who argue that society has moved beyond the mass-produced, standardised models that Ford automobiles used to epitomise. Mass production and mass organisation have reached their limits. Mass society, with mass working class movements such as trade unionism, is breaking down. Instead we are seeing flexible, customised production and new social movements, often of a local kind. Tomorrow (LexiCon, 2000) argues that central to 'new times' is a more personalised relationship between organisations and people.

Each of these spotlights need to be shone together to see the full picture.

What will drive these changes?

When they talk about forces of change in the advanced world, most experts refer to globalisation, post-modern values, demographics and technology. Each of these will accelerate the arrival of the it-must-fit-me world.

Globalisation involves the interlocking of nations so that they begin to form a single unit. It will persistently widen markets and create economies of scale. Big will get even bigger, allowing endless new brands to find their niche. This will widen people’s choice. Only two or three people in a city may like a particular song, but if it is two or three people in every city throughout the world then that becomes a sizeable audience! Individuals will be offered a stunning expansion of routes to personal fulfilment.

Post-modern values include the rejection of hierarchy, suspicion of institutions and strong emphasis on personal choice. They have largely grown out of the inconsistency of mass society. The mass world expanded the range of choice — you could choose between ever more options — but continued to treat people in a standardised way. People were left dissatisfied.

Inevitably, once they had some choice they wanted more. Having tasted choice they became irritated by one-size-fits-all and suspicious of top-down organisations which squeezed them into a mould. Mass society contained the seeds of its own demise. The post-modern mindset took hold — and is now itself a force for change. It is highly receptive to personalised scale.

Demographics will be important, first because older people will be more numerous — and also more affluent. They will have had a lifetime of rising consumer expectations. So they will be delighted to spend their time and money on more personalised products, which will jack up their expectations further. They certainly won’t want uniform treatment.

Secondly, younger people will be better educated, with many more staying longer at school and going to university. Higher education tends to take working class people beyond their background, by equipping them for better paid jobs and exposing them to a wider range of values. More young people will have the money to pay for a personalised lifestyle and will be set free from the traditions of home, free to choose between the values of the emerging world. Sadly, the poor will be left behind.

Technology will continue to make personalised scale possible, symbolised by the Internet itself — the more people who use it, the more each person can find precisely what they want.

New age, new mindset

As we gallop towards the it-must-fit-me world, people’s mindsets will change. If your drugs fit you exactly, if your mortgage fits your exact circumstances, if you can find precisely what you want on the Net, you will end up expecting everything to fit you exactly.

"Well, it’s not the same with the new minister. Church isn’t what it used to be. (It doesn’t fit me exactly any more.) Time to move on.' 'My marriage doesn’t feel quite the same (she no longer fits me exactly). Perhaps we should separate.' The attitude has already crept up on us. It will become yet more pronounced.

If you want to know how people will be thinking as we dash into the new century, 'it must fit me exactly' is the answer. It will be the defining outlook of personalised scale.

From 'it-must-fit-me' to 'I must fit you'

It is an attitude that will sideline the Bible’s central concern with justice. If people’s reference point is what fits them perfectly, there will not be much room in their hearts for those who feel socially edged-out and who cannot afford it-must-fit products. We risk becoming a more selfish society. This makes the task of evangelism and discipleship even more urgent. How can we revolutionise our culture with the gospel of grace — a gospel that transforms 'fit me' into a willingness to fit others?

But it is also an attitude that echoes parts of the gospel. God who is infinitely great wants to connect with us in a personalised way. He wants his love to be made-to-measure — to draw out the best in us and help us achieve our potential. He doesn’t want my relationship with him to be precisely the same as yours. That is why Christians have such different experiences of God. God’s love fits each person exactly.

So as we speed into the new century, the challenge for the church will be to help people see how their it-must-fit-meexactly mindset resonates with parts of the gospel, to walk with them on their journey into Christ’s love and to stand by them as this love, painfully sometimes, transforms their expectation from 'It must fit me' to 'I must fit you'.

A church that fits?

To do this the church itself will need to change. By and large, the church is still stuck in the standardised world. It approaches evangelism with a mass mindset. 'Come and join our church' is the invitation, which assumes that 'our church' is suitable for the people we invite. 'We like it so other people will.' That is typical one-size-fits-all thinking.

The church could get away with it in mass society, but in an it-must-fit-me world it won’t wash any more. A different approach is needed — one that is more sensitive to the differences between people, to their suspicion of organisations and to their expectation of choice. The reaction of other organisations is to draw closer to people, to listen to them and to respond to their individual preferences. Can the church afford to stand aloof?

In 1995 an Anglican and a Baptist church in Bristol, England jointly launched a three monthly 'seeker service' for older people who did not come to church. The services included drama, an interview, two well-known hymns, a secular song on the theme, and tea - loads of it. They discovered three specific needs — a place to belong, a sense of family and a place which is linked with hope for the future.

Those who came wanted the seeker services more often. That was not practical, but a small team started a fortnightly Focus Group with a simpler programme — generally a speaker, sharing family news, a hymn and some prayer, followed by food. Here was a realistic response to the needs of a specific group of people. Instead of hoping that older people on the fringe would come to established church, church was built round them and their particular needs. Church was 'customised'.

Was this a sell out to consumer values? Or was it the church becoming more people-shaped without losing its God-shape?

footnote:[Notes

3 Sumantra Ghoshall and Christopher A. Bartlett, The Individualised Corporation, Heinemann, 1999.

5 Charles Leadbeater, Living on Thin Air, Penguin, 1999, p. 18.]

CHAPTER THREE: CHOICE BUSTERS

At the end of a talk about tailor-made consumerism, one person exclaimed, 'Don’t you agree that what Mike has given us is not a vision of the future, but a vision of sheer hell! All this choice! How on earth will we cope?"

Option paralysis

It was a good question. As organisations relate to people in a more personalised way, we shall face a torrent of choice. Which school shall I send my child to? Should my holiday have an educational focus or shall I just chill out? Would I prefer to have physiotherapy or try an osteopath? Where shall we eat tonight? Critics will complain that many of these choices will be trivial or manipulated, but even so we shall still be bombarded by choice.

Choice has become central to the new style of 'democratic' parenting. It is no longer 'Time for tea kids, it’s hamburgers' but, 'What would you like for tea tonight, hamburgers or hotdogs?' Children are showered with alternatives. They are growing up with choice central in their lives.

Of course choice fatigue has not hit everyone. Many people are denied choice because of poverty and other forms of

Shades of the it-must-fit-me world

The 2020 church also mirrors the two sides of personalised scale. Size and customisation come together. Cooperation between local churches enables church as a whole to harness the benefits of scale. Established congregations can pool their resources of prayer, money, gifts and time. These are then used to support fresh forms of church, built around particular groups of people.

Church is better placed to help people with their everyday choices — to become an 'agent'. That is because it is more focused on specific groups than traditional church: it is closer to people and is taking the trouble to research their needs. In particular, it is more sensitive to the differences between people in their work and their consumer settings, and has begun to develop distinctive approaches to each.

Standardised church is a glint in a rear-view mirror. Today we have an it-must-fit-me church for an individually wrapped world.

In your dreams?

Connected fragments were the essence of the New Testament church. They are typical too of 'Nottingham in 2020'. The latter is not perfect, but it has a heart for the socially excluded, it connects with different sections of society, there is unity in its diversity and — not least — Christianity has made a comeback. Is it wishful thinking, or could this be a glimpse of the future?

footnote:[Notes

1 Kees van der Heijden, Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation, Wiley, 1996, pp. 199-202.

2 Robert Banks, Paul’s Idea of Community, Paternoster, 1980, pp. 39-40.]

CHAPTER EIGHT: FRAGMENTS OF TOMORROW

Dreaming is all very well, but was 'Nottingham in 2020' no more than that? The answer is that in Britain new forms of church are being trialled — not in large numbers, but enough perhaps to sketch the faint outline of a picture not so different from 'Nottingham in 2020'. Might church be on the edge of a dramatic new future?

The end of clones?

Church planting is one part of the picture. It involves reaching into new networks. Few people from a housing estate attend their local church for example, so a new congregation is formed among them. Or a new congregation is planted in a school to reach an unchurched network of families. Typical church plants are targeted at particular groups of people.

Our mould for you

In recent years all the major denominations in Britain have placed considerable emphasis on church planting. The Archbishop of Canterbury gave it his blessing at a conference in May 1991. The Elim Pentecostal Church has had a special focus on church planting, especially in north west England. Kensington Temple has started many new churches in and around London. Various new church streams see church planting as a crucial method of evangelism. [12]

But many of these plants have failed to realise their potential, and the number of new plants has declined in recent years. Often plants have been replicas of existing congregations, or reactions against them. [13] Instead of moulding the plant around the people it was designed to attract, newcomers have been expected to fit into a model that suited the Christians setting it up. The core either copied what they already had or sought to create what was missing from their 'home' church.

The new congregation was not built with, let alone by the people it was seeking to reach: it was designed for them. And very often the design did not fit, so the expected newcomers failed to arrive. Plants were not sufficiently personalised to the target group.

We listened to the wrong people

In the early 90s, as a minister in Taunton, I made exactly that mistake when we established a new 'Family Praise' congregation. Most of the people behind it were long-standing Christians. They wanted more informal worship than was available in our other services, and a longer sermon.

One or two people had a more radical vision. They wanted to build a congregation round people who did not come regularly to church, but were on our fringe. The congregation would have been very informal indeed, the music would have been more low key and the 'sermon' (if that’s what it was) would have been bite-sized and taken less for granted. The congregation would have developed flexibly, acquiring its own style as it found its feet.

This was certainly not what the established Christians wanted, and with my support they won the day. The new congregation attracted a few on the fringe, and even more regular worshippers from other churches, but it was not a great evangelistic success. We had first decided what we wanted, then invited others to join. Perhaps we would have done better to have thought more carefully about those on the fringe.

Are lessons being learnt?

Bite-sized churches

Spurgeon’s College and Oasis Trust are placing teams of mainly young people in under-churched areas of East London. They live and work in the area, getting involved in youth clubs, football clubs and community activities. They worship in homes, but refuse to use the term church till it is given to them and owned by local people. One group didn’t give themselves any name, but waited for people in the area to name them. The name their neighbours eventually settled on, Cable Street Community Church, came as a surprise. Here is one bottom-up approach to church planting which could be a model for the future. [14]

Teen churches

My church in Taunton must have been one of the first churches to establish a teenage congregation. Launched in 1991, we called it Nite Life. In its heyday it attracted up to 150 teenagers on a Sunday evening. On alternate Sundays the programme included a celebration, followed by a non-alcoholic bar, games and other activities. On the intervening Sundays the young people met in small groups, each led by one of their peers supported by an adult in the background.

It was incredibly hard work! There were all sorts of problems, and after several mistakes numbers dropped to 40 or less. So we decided to reinvent it. The young people gave Nite Life a new name, we involved them more closely in the design, we changed the venue, we worked more effectively with other churches, we staffed it more adequately and in 1996 we sprang it on the town as "Uncaged'. Again it was a huge success for a while.

Peer pressure for church

Teenage and youth congregations of various kinds can now be spotted all over Britain. One estimate in 2000 put the total at around 100. They include the 'Soul Survivor' network of youth churches (headquarters in Watford) and Revelation Youth Church in Chichester. Growth from a handful to a hundred in a few years is not bad! The figure may be much higher. The 1998 English Church Attendance Survey (completed by a third of all churches) found that one in seven held a regular youth worship service, with an average attendance of 43. [15]

A great advantage of these congregations is that peer pressure can work in the church’s favour. A fourteen-year-old looking round a traditional youth group of ten will not find it hard to conclude that he really is the exception. Scarcely anyone else from school is there. But attending a high-voltage youth congregation of a hundred plus is very different. 'This is a happening place!"

We can’t expect teenagers to worship regularly with adults when they are separating from parents and reacting against adult life. Nor should we let them drift away from church because there is nothing for them. Is it not better to allow them to rebel against adult church by forming their own congregation in which their distinctive spiritual needs can be met?

Doing it together

But teenage congregations can be immensely difficult to sustain. They are inherently unstable — youngsters come and go and make all sorts of demands. They require close supervision, but of a kind that allow teenagers plenty of space. Adults need to understand youthwork, which these days means that at least one adult member per congregation will be professionally trained. For these and other reasons, teenage congregations usually require a number of churches to work together. Few churches have the resources to go it alone.

Teenage congregations can stem the flight of young people from church and attract youngsters who are totally unchurched. They could help revive the church if adults captured the vision, worked with other churches, made resources available and allowed teenagers to discover church for themselves.

Seeking or serving?

A very different beacon has been experiments with seeker services, inspired by the Willow Creek Community Church in Chicago. Willow Creek uses drama, music, audio-visual media, testimonies and 'issue-based' preaching to create presentations to audiences rather than participatory events. These services for 'unchurched people' are the main activities on Sunday, with worship and activities for nurturing faith occurring midweek. A number of churches in Australia, Britain and the United States are trying something similar.

At your service?

The Willow Creek mission statement, 'A church for the unchurched', expresses the priority given to non-members over members. The use of modern media in the presentations illustrates the commitment to cultural relevance. 'Process' rather than 'crisis' evangelism is highly prized: Willow Creek accept that people enter faith over time, offer an explicit welcome 'regardless of where people are at on their spiritual journey' and seek to work patiently with them. They have an 'Axis Service' tailored specifically to the needs of 'GenX'.

Too sales savvy

However, one danger is that Willow Creek imitators will get locked into a 'we’ll organise a presentation for you' mindset — believers 'market' the gospel to non-believers. This may become tough-going as people become increasingly suspicious of organisations that try to sell them things.

Winston Fletcher, a leading UK advertising executive, reckons that by the age of ten, children will have seen 50,000 different commercials about half-a-dozen times each. This is breeding adults who will be so distrustful of sales campaigns that they will flit from one brand to another. Marketers fear that customer loyalty is becoming a thing of the past.

Slick presentations of the gospel to unchurched audiences risk the response, "You are just like any other organisation trying to sell me something.' Instead of generating 'customer loyalty' to Christ and his church, they may feed a consumerist pick-and-mix reaction. 'That was all very interesting. I liked what you said about relationships. I’ll add that to my way of thinking' rather than, 'I feel grasped by something here. Do I need to change my way of thinking?'

Meeting people on their own turf

It is said that Willow Creek is most effective in reaching people who used to attend church or still come occasionally. [16] It seems to have less impact on those who have never been to church, a segment of advanced society that is growing rapidly. Is this because, despite its commitment to relational evangelism, it relies on a 'sales' approach that in the long-term is doomed to failure in our consumer-savvy world?

Marketers realise that if people are to trust an organisation they need to be convinced it is on their side. This applies as much to church as it does to Canada Life. Prepackaged presentations of the gospel won’t cut much ice with people who are shaped by a culture that is profoundly suspicious. The new generations are wary of becoming committed lest they are betrayed, hurt or squeezed into a mould. They are most likely to be committed if they feel it is their church.

So how can the church persuade the unchurched that it is on their side? Encouraging non-believers to feel some kind of ownership of the church as they travel into faith is vital. Witness must be self-evidently altruistic. Christians must become not recruiters but friends — fellow-travellers, admitting that their knowledge is partial and their obedience inconsistent. Such frankness, says church growth professor Eddie Gibbs, will strengthen our testimony among those who look for honesty and authenticity. [17]

Willow Creek’s commitment to cultural relevance has much to teach the wider church. But instead of being 'church for the unchurched', Willow Creek’s imitators might do better to become 'church of the unchurched'. This would involve drawing closer to non-believers, sharing more of their lives and crucially, if they are willing to explore the Christian faith, giving them more freedom to develop expressions of the church that best suit them.

Willow Creek itself has an extensive programme among the poor. Why not encourage a group of poor people to form their own congregation rather than attend what may look like someone else’s middle-class church? Perhaps people need to feel they belong to church before they are asked to join.

Belonging before joining

There is an element of being church before you have joined in Alpha, the ten-week introductory course to Christianity which involved over 6,300 UK churches in 1998-99. During an Alpha evening there is a presentation of the gospel, but the emphasis is on building community.

Groups that won’t go away

The evening starts with a supper, next there is the presentation and then people break into small groups, supposedly to discuss the presentation. In practice, the groups have no fixed agenda. Members can talk about what they want, and if they would prefer to adjourn to the pub for instance they are free to do so. It is within these groups that often new friendships are formed, mutual support develops and people begin to have an experience of church, even though they may not describe themselves as Christians. Church is customised to the group.

Once the course is finished, however, people are encouraged to attend normal church on Sunday. Some make the transition, but quite a few don’t. All round the UK — in Hampshire and Oxfordshire for instance — there are examples of Alpha groups continuing to meet for worship, prayer, teaching, fellowship and pastoral support, but not going to regular church. The rest of the church longs for them eventually 'to join us', but it may be that they won’t make the leap. Will they peter out because they are not adequately resourced, or will they continue with an existence divorced from the wider church?

Alpha congregations?

One or two Alpha courses are beginning to emerge as new congregations in their own right.

Christ Church, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales is planning a church plant in 2001. They have been promised a minister to oversee it, and it will comprise almost entirely people who have completed an Alpha course. The congregation will meet either in a school or a pub, there will be no prayer book or formal liturgy, it will feel very different to normal church, but it will retain links with the sending congregation. Instead of expecting Alpha graduates to attend traditional church which feels strange and culturally alien, they will form their own congregation in a style that suits them.

In September 1998 Holy Trinity, Margate established a separate church for people in the Alpha culture. New people had been coming to Holy Trinity, quite a few through Alpha courses. There was tension between these newcomers who wanted a more relational church, and those who were rooted in traditional Anglicanism. As a solution the diocese invited the minister, the Rev’d Kerry Thorpe, to establish a separate church, in a nearby school, for Alpha graduates and others who preferred something less traditional. The new church focuses on small, midweek groups who also meet together on Sunday — a classic cell-church model.

Could these examples herald a trend? Why bust a gut trying to persuade ex-Alphas to join mainstream church which has little appeal? They are already coming to a group midweek, enthusing about it and beginning to make the Christian journey. So why not encourage some of the larger groups to continue meeting during the week and to experiment with what it would mean for them to be church? In due course members could be taught about Christian giving, and be invited to help pay for a minister either to lead their group or start a new one. A new congregation would be in the making.

It would take the bottom-up, community element of Alpha to its logical conclusion. And it might work not only for Alpha, but for the Emmaus course and others like it.

Church at work

Imagine a large Alpha course, perhaps in London, nearing its end. Instead of being invited to a follow-up Alpha and to Sunday church, participants might be asked, 'Many of us have been enjoying ourselves together and some of you have been journeying into faith. Would you like to experiment now with being church? We realise that many of you are turned off by traditional church, so why don’t we continue to meet and pioneer

together a form of church that works for you? Why don’t you show us how to do church?"

Church will train you — and employers will pay!

'As part of this, the invitation might continue, 'why don’t you tell us what issues you face at work? We’ll then use our networks to find expert Christians to provide training events for you and your friends. Whatever the topic - combatting stress, managing change, improving people-management skills, or getting up to speed with the latest health and safety regulations — we’ll find a specialist to teach you best practice. Then at the end they’ll offer an optional session on spiritual resources that can help you to practise what you’ve just learnt.

'Here is a way for you to take Christianity into the workplace. It will help you to discover how what you’re learning here on Wednesday evening can make a difference to Thursday morning. It will be something you can offer to your friends, so that all of you are more effective at work. It will be an easy way of introducing your friends to church. And it will be free — because as a training course employers will pay!"

Weekday church, held near people’s places of work and addressing issues of work, has huge potential. Everyone has colleagues at work, many of them are under tremendous pressure, and there is a growing market for training courses that go beyond functional skills to address values and emotional well-being. Employment-based networks would work to the church’s advantage.

Ingredients for a new mix

Is this an unrealistic dream? The ingredients are coming into place. Workplace church is rising up the agenda. In the City of London quite a few Christians meet in groups during the week, and are beginning to ask whether they can bé church in a fuller sense. Pressures of work, not least the number of hours involved, make it difficult for many of them to be involved with church back home.

The workplace is becoming all-embracing, taking over more of people’s lives as employers provide fitness centres, creches and other facilities. Some Christians are asking, 'If the workplace is becoming so important, shouldn’t the church be more involved?' Others are wondering if God’s interest in work can be given a more concrete expression by letting church flower more fully at work. All this is moving slowly in the direction of workplace congregations.

In London’s Docklands a group of Christians meet every Wednesday, For many of them this is not worship as well as on Sundays, but instead of Sundays. It seems effectively to be evolving into a workplace congregation. [18] ASDA in Liverpool open half an hour later one morning a week so that their staff can attend communion first.

More and more people are finding midweek worship — in a variety of settings — attractive. In England it has become a significant trend. [19] As the recognition grows that Sunday church does not suit all Alpha graduates, midweek churches, building on successful Alpha groups, could prove one solution. Perhaps initially they will be based on larger Alpha courses which have enough 'critical mass' to make a new congregation viable.

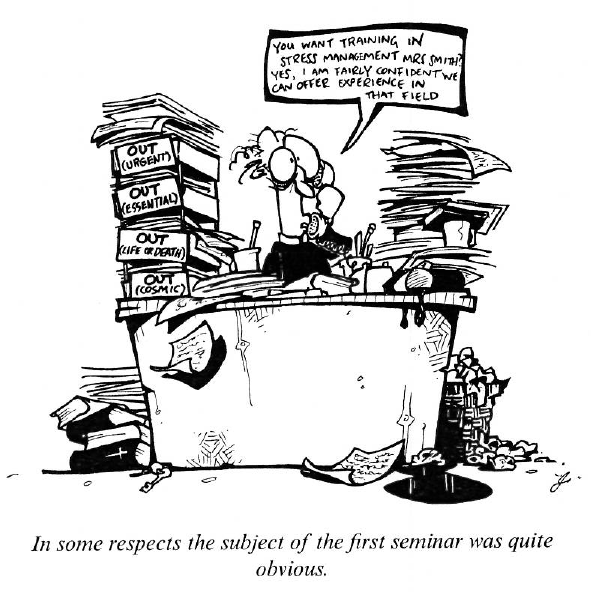

Dr Bill and Frances Munro run stress management courses for a variety of organisations, including Britain’s Inland Revenue. At the beginning of each one they promise to introduce participants to techniques that will help them reduce stress. 'At the end of the day,' they continue, 'we’re going to offer you a one hour optional session. You’re free to leave before it starts, but if you remain we’ll show you some spiritual resources that will help you to put into practice what we’ve taught earlier in the day.' They find that 60% to 70% of people stay behind for a simple introduction to Christianity. [20]

Pulling these elements together would create a highly effective model for workplace church. Congregations would meet during the week, be close to people’s places of work and minister to the workplace through training courses, mentoring and by other means. Could this, too, be part of the future?

'On a Council Estate in Dartford, Kent an Anglican vicar started a service on Wednesday mornings. Matins at 9.30am. Whoever would come? About 25 mums regularly attend, the time convenient as they can arrive after they’ve dropped their children at school. They do not come to church on Sunday, because their husbands don’t want to be tied to looking after the children in their absence.

Such stories could be multiplied many times. The English Church Attendance Survey asked respondents if they had a regular midweek worship service. 42% replied YES . . . In 1979, 37% of churches held at least one midweek meeting . .. However, these included any kind of midweek meeting, such as house groups, prayer meetings, etc. as well as worship services, whereas the ECAS question was specific. Nevertheless some of the 37% would have included worship services, though the percentage is unknown and would have been lower.

It means that over the two decades in between, the percentage of churches holding midweek worship services has increased. Perhaps by 2003 many more churches will be having midweek worship services! [21]

Reaching its cell buy date?

[22]

Cell churches are attracting a lot of interest in Britain and other parts of the world. It is a way of doing church that centres on the small group. A local church will comprise a group of cells. Each cell typically has eight to fifteen members, meets weekly and provides what most traditional churches offer — welcome, worship, word and witness. It includes ministry, teaching (cells in a church often use the same material), Holy Communion, Baptism and pastoral care.

Cells and celebrations

A celebration, drawing the cells together, meets regularly but not necessarily every week. It is important but, unlike traditional church, is not the focus. Cells are the essence of church. The emphasis is on relational evangelism. The priority for each cell is to attract new members. When it has reached a certain size, the cell divides. Multiply and grow is the aim.

This is not without its problems. A well-bonded cell may have a life and culture that non-believers find difficult to break into. Established members may be further along their faith journey than enquirers, who feel out of their depth. Newcomers are expected to join what already exists, but often they don’t fit so they do not stay the course. Church is not built round them.

Even so, cell churches have been effective in some places. [23] Cells provide community and friendship in the midst of a lonely society. The combination of small group and large celebration echoes the 'Nottingham in 2020' vision of fragments linked to a larger whole.

Cell churches certainly have a place in tomorrow’s landscape, but will they be so preoccupied with their cell life that the celebration is as outward looking as they get? Will they be able to join hands with other churches?

Dismembered body or linked arms?

If tomorrow’s church was purely customised, it would be a disaster. Fragments of church would be scattered all over the place, but nothing would draw them together. Each church would be a niche, catering for a particular group of people in its own way. Where would the whole body of Christ find expression? The body would be dismembered.

Prayer nets — the new fashion

One of the exciting movements in Britain today is the burst of network prayer around thecountry. Most large cities—and many towns — now have an integrated prayer net, drawing Christians together from across the denominations. Manchester’s Prayer Network for example covers the whole city and has been meeting quarterly. So many churches have got involved that it has had to break into independent networks for each main borough. In Loughborough all the churches came together for a mission in 2000, with 40 community prayer cells organised ecumenically. Christians from Brazil and Argentina get very excited when they see what is happening. Revival in their countries was preceded by a similar upsurge in prayer. Could God be using this prayer explosion to prepare the ground for a spiritual breakthrough in Britain? There is a mounting sense that this prayer phase needs to move into a harvest phase, but there is also some uncertainty as to what this might mean in practice.

The end of do-it-alone

There are other concerns. A number of the networks have a strong revivalist theology and a charismatic style that other churches find off-putting. There is a genuine desire by the prayer nets to draw in others, but often they lack the language and theological flexibility to make this possible. Justice is high on many of their agendas, and this may make it easier to enter into partnership with liberals and catholics. Would a more radical, twenty-first century approach to mission also help to build bridges?

Few churches have the resources to reach out to all the groups in their area. In our networked society, often people belong to networks that jump across geographical boundaries. If a church ploughs its own locality alone, it will keep unearthing parts of a network, but each part will be too small to support outreach designed specifically for it. Carve a network into geographical segments, and the pieces are too minute to be the focus of mission. But join the pieces up, and a mission tailored to the group may become possible. Churches have to work together.

Collaboration is taken for granted in the world at large. Will prayer networks make it easier within the church?

Tomorrow’s church today?

A variety of developments, then, potentially challenge existing ways of being church. It is as if pieces of the jigsaw are lying on the table. They are all different. Church planting is learning how to be 'bottom-up'. Teenage and youth congregations come in all shapes and sizes. Willow Creek has modelled cultural relevance. Alpha congregations may be on the horizon. The ingredients exist for innovative forms of work-based church. Cell churches model fragments coming together and being resourced by the larger whole. The spread of prayer nets may be saying goodbye to 'I’ll do it on my own'.

Fit these pieces together and a picture begins to emerge of church becoming more geared to the fragments of society, with hints of greater cooperation at the same time. Might this herald a new vision for church?