A reader's guide to transforming mission

Stan Nussbaum

- 40 minutes read - 8386 wordsChapter 2: Disciple-Making

Matthew’s Model of Mission

(Bosch, TM, pp. 56-83)

Then Jesus came to them and said, "All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age."

(Matt. 28:18-20, NIV) [1]

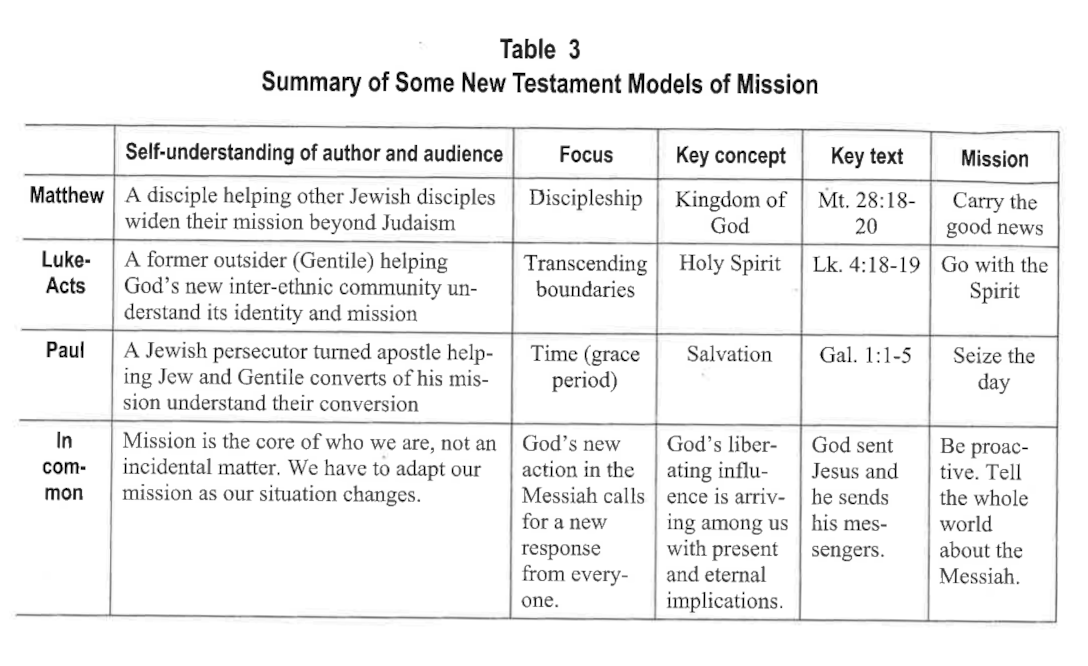

Note | For a preview of the next three chapters, see the summary in Table 3 (p. 42). |

This "Great Commission" is so often quoted in mission circles that it tends to take on a life of its own. "The 'Great Commission' is easily degraded to a mere slogan, or used as a pretext for what we have in advance decided [that 'mission' should mean]…. Matthew 28:18-20 has to be interpreted against the background of Matthew’s gospel as a whole" (57.5).

What then does the Great Commission mean if we see it in its proper perspective as the text that draws together "all the threads woven into the fabric of Matthew" (57.5)? We will not know unless we consider first the community of people for whom Matthew wrote and the burning concerns of the place and time for which the Great Commission was originally designed. [2]

Matthew’s purpose in writing was "to provide guidance to a community in crisis on how it should understand its calling and mission" (57.9). The community was probably a group of Jewish Christians who had moved out of Judea into a Gentile setting, possibly Syria. In the 70s or 80s AD (following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem), this community was facing an identity crisis: "Who are we? Are we really 'Jewish'? What are we doing here outside our homeland? Do we have a mission to our fellow Jews? Do we have a mission to the Gentiles among whom we live now?"

In the midst of such questions, Matthew set out to write a gospel that is not merely a biography of Jesus with a missionary command conveniently tacked on at the end. Instead, from start to finish Matthew’s Gospel is an attempt to help a community of Jesus-followers discover their new identity as Jews-witha-mission or Jews-for-Gentiles. The discovery is rooted deeply in their Jewish heritage yet it enables them to engage the Gentile world not primarily as Jews but as messengers.

This new disciple-making identity is so paradoxical that Matthew appears almost self-contradictory when he describes it. At many points the story he tells seems very pro-Jewish (59.9):

beginning the genealogy of Jesus with Abraham (1:1)

mentioning that the disciples' first missionary assignment was restricted to Jews only (10:5)

constantly quoting Jewish prophecies as if all his readers know and believe them (e.g., 27:9-10)

At other points the story sounds very pro-Gentile, such as in the wide range of Gentiles held up almost as heroes because they hail Jesus properly:

the "wise men from the East" at his birth (2:1-12)

the centurion who trusted Jesus to heal his servant with only a word (8:5-13)

the Canaanite woman with the demon-possessed daughter (15:21—28)

the centurion at the cross (27:54).

At the end of the day, Matthew calls on his readers to engage in mission to both Jews and Gentiles. To make disciples."'of all nations" does not mean "of all Gentile nations." It means "of Jews and Gentiles alike" (64.5). From a Jewish perspective this implies a staggering redefinition of the identity of God’s chosen people. Jews and Gentiles are placed on a par with each other before God and before Matthew’s community. Something has happened in the light of which Jews and Gentiles look "alike"! What on earth could it be?

The arrival of the "kingdom" in Jesus has redefined everything. This earthshaking fact is the beginning of Jesus' preaching (4:17), the constant theme of his teaching (e.g., chap. 13), and the basis and heart of the Great Commission (28:18-20). The arriving kingdom is a new cosmic reference point, the basis for all personal and group identity ever since Jesus announced it. Whoever is oriented to this point is transformed into a disciple and a missionary.

The word "kingdom" does not occur in the Great Commission but the idea clearly does in two ways. First, the often-overlooked basis for the Commission kingdom is inaugurated, go and make disciples. …" Second, "teaching them to obey…" is in effect, "teaching them to live as loyal subjects in my kingdom."

On the surface this may sound like our mission is to impose on the world a new law in the name of a new Moses (65.5). If we claim to announce a new kingdom and not a new legalism, what exactly is the difference between our mission of "teaching them to obey" and the teaching of rules? This is absolutely crucial for understanding mission according to Matthew.

First, the "teaching" that Matthew has in mind is neither indoctrination nor academic instruction. It is more what we would mean today by "shaping" or "formation." "Shaping them to obey all that ! have commanded" (66.8).

All the "shaping" involved in our teaching is based on a deed, not an idea, a command, or an oracle. The deed is God’s deed, sending the Messiah to announce and establish the kingdom. Our good news is the good news of the kingdom (4:23, 9:35). Our fundamental message is not, "Follow these rules," but "Come to terms with this wonderful God-deed."

The authority behind Jesus' commands was not the typical authority of Moses and the prophets, "God said so," but rather, "God is doing so." The teaching of Jesus about the central God-deed (the arrival of the kingdom) was proved by many deeds of Jesus (11:2).

To "obey" this deed-based teaching is the same as to reorient one’s whole life to face these deeds or facts. Reorient means to turn, i.e., "repent" (4:17). Such reorientation does not mean "Come inside the fence marked off by these boundary rules," but "Turn your life around and walk out through the gate into a wide-open, new world of life." The goal is liberation, not forced conformity.

Getting reoriented to the ultimate God-deed is liberating because the ultimate God-deed is not a cold hard fact. It is a living, breathing fact —a person. "To encounter the kingdom is to encounter Jesus Christ" (71.1, quoting Senior and Stuhimveller). If the center of our life is a person, not a law, the tone of our life cannot be legalistic. We are subjects of a king, not dehumanized objects who must have our goodness measured by some abstract standard.

Even though they are not oppressed into conformity, those who welcome the teaching about the kingdom really do "obey" and change. As they enter the reign/kingdom of God, the influence of God transforms them from the inside out. They are captivated, spellbound, overwhelmed by a force they just can’t get enough of. They show a "righteousness" or "justice" higher than that of the Pharisees (5:20), yet they cannot claim to have achieved any of it by their own goodness (72.7).

When they obey, the followers of Jesus prove nothing about themselves

obey him, the kingdom has not arrived and Jesus' announcement of it is a lie. Therefore his followers cannot dodge or explain away the ethical teachings of the Sermon on the Mount (chaps. 5—7), though that has often happened in church history. "Jesus actually expected all his followers to live according to these norms always and under all circumstances" (69.8).

If we understand the kind of teaching Matthew was talking about, we understand what he meant by a mission of "making disciples." The impact of this kind of "teaching" is discipleship, and a special kind of discipleship at that. When we receive and act upon the teaching of the reign/kingdom of God, we are not merely followers of a wise rabbi (teacher). We are followers of a king, one whose forefather is David, not Moses or Aaron (75.7). The necessary outcome of his teaching is discipleship, not churchmanship, that is, an internally transformed life made plain in everyday conduct, not an external conformity to a fixed pattern of religious practice.

The command to "make disciples" serves as the connecting bridge between the original circle of disciples and each successive generation of the ever-widening church on its mission. This means that all true disciples have an essentially missionary identity. "The followers of the earthly Jesus have to make others into what they themselves are: disciples" (74.4).

Weakness, suffering, and failure may still be facts of life for the disciples as they obey the Great Commission, just as they were for the disciples when Jesus was among them in person. However, the Great Commission is less a command reminding us how badly we are falling short than it is an empowerment creating what it requires, speaking it into being. "Jesus rules! Go let people know!" "Nobody who knows this can remain silent about it. He or she can do only one thing — help others also to acknowledge Jesus' lordship. And this is what mission is all about — 'the proclaiming of the lordship of Christ' " (78.6).

As we proclaim him, we testify not to his memory or his ideas but his presence. He is "God with us" (1:21, 28:20), the propeller of life-changing mission to the end of the age.

YOUR VIEWS AND YOUR CONTEXT

9. What does one realize about mission if the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18—20) is interpreted in relation to the whole of Matthew’s Gospel instead of as an isolated quotation?

10. If Matthew has made a clear distinction between discipleship and legalism, how have so many churches and Christians missed it and become legalistic? What are they missing when they read Matthew?

11. How would Matthew’s good news have had to change if Jesus had been a descendant of Moses or Aaron (tribe of Levi) rather than David (tribe of Judah)

Chapter 3

Transcending Class and Ethnicity Luke’s Model of Mission

(Bosch, TM, pp. 84-122)

"The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to release the oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor." (Luke 4:18-19)

While it is true to say there is really only one mission described in the New Testament, it is also true that the one mission looks quite different when viewed from different angles. We have seen it from Matthew’s angle. Now we turn to Luke (both the Gospel and Acts) and then to Paul in order to appreciate other dimensions of the complex reality of mission.

As we turn to Luke, we shall adopt the same approach we did with Matthew, looking at his key mission texts in the context of his entire work rather than isolating them as mission slogans. Reducing our mission thinking to a slogan is areal danger. Evangelicals have tended to use Matthew’s Great Commission as their slogan and focus on individual conversions and church growth. On the other hand, ecumenicals generally and liberation theologians in particular have tended to use Luke 4:16-21 as their slogan (84.7) and focus on social transformation. Let us dig a little deeper into Luke’s writings and see for ourselves what he is really saying.

In Luke 4 (quoted above), Jesus reads to his hometown synagogue from Isaiah 61 and then stuns his hearers by announcing that Isaiah’s very down-to-earth messianic prophecy was fulfilled that day. Before they can recover from the first shock, he delivers a second one, implying that the messianic wonders would somehow come without God taking vengeance on the enemies of Israel as expected. [3] In fact, in this messianic kingdom God would bless outsiders, possibly even in preference to his own people Israel! (Luke 4:23-27). The crowd would not bear that reinterpretation of Isaiah’s prophecy, and they almost killed Jesus for daring to suggest it (Luke 4:29-30),

Luke does more than suggest this idea. The theme runs right through his two-volume work (the Gospel and the book of Acts). The good news is that God’s vengeance on the nations has been suspended while God goes on an all-out mission of gracious forgiveness, inviting outsiders to seats of honor at the messianic banquet table (108.5).

Before we examine Luke’s Gospel and his view of mission in more detail, we need to consider his audience. It appears he, a Gentile, was writing primarily to Gentile Christians in the decade of the 80s, that is, after the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans. Jesus had not returned in the lifetime of the apostles, as had been widely expected. Gentile Christians were facing questions such as, "Who are we really? How do we relate to the Jewish past? Is Christianity a new religion? And above all, how do we relate to the earthly Jesus, who is gradually and irrevocably receding into the past?" (85.9).

As a historian and a theologian, Luke answers these questions by helping the Christians of his day see their lives as one stage in the flow of God’s activity in the world — past, present, and future. They were in continuity with previous stages but they also had a present missionary identity because they could foresee the stage God was bringing into being. They were both the product of mission and the bearers of mission. They were like iron filings that under the influence of a magnet had become magnetic themselves. We can understand their magnetism and their mission by examining three of their key questions.

WHO ARE WE?

We Christians are the multiethnic, multi-class community that came into being because God suspended his vengeance on all nations and sent his deliverer to Israel. Our community is an anomaly among the nations of the earth because of the way it transcends social class and ethnic identity. We need to understand both how this leveling of class and race works among us and what message it sends to the world.

How class and ethnicity are leveled by the good news

Every key aspect of Luke’s missiology has a leveling or boundary-transcending effect.

There is only one Messiah for all the nations (Acts 1:8).

Repentance and forgiveness are the same route to the same salvation regardless of ethnicity or class (Luke 24:47),

The coming messianic banquet (Luke 13:28-30) may be the greatest leveler of all, where people of all classes and nations sit down to eat and celebrate together. With this feast as the envisioned end of mission and history, the familiar human dividing lines of class and race are transcended. They simply cannot mean very much any more.

The leveling theme jumps out at the reader constantly in both the Gospel, where economic class is the main barrier to overcome, and Acts, where ethnicity is the hurdle. Let us look more closely at both.

The Gospel of Luke is preoccupied with "the poor," that is, "all who experience misery" (99.3). We have already seen this in Jesus' announcement in Luke 4:18, the "good news for the poor." Many other passages stress this theme of God’s love for the poor and his plan to turn the tables on the rich (1:53, 3:10—14, 6:20 and 24, 12:16-21, 16:19-31, 19:1-10; see 98.3—-99.4).

Unlike many who (mis)quote him, Luke does not conclude that a pro-poor gospel must be anti-rich. In fact, Luke has even been called the "evangelist of the rich" (101.8), not in the sense that he makes the way easy for them but that he deliberately addresses them as a redeemable group. He "wants the rich and respected to be reconciled to the message and way of life of Jesus and the disciples; he wants to motivate them to a conversion that is in keeping with the social message of Jesus" (101.9, quoting Schotroff and Stegemann). Zaccheus (Luke 19:1-10), Barnabas (Acts 4:36-37), Lydia (Acts 16:13-15), and others in Luke’s writings are model converts among the rich.

As the Gospel of Luke emphasizes the poor, the book of Acts emphasizes the Gentiles. Nothing can be clearer from Pentecost than the fact that God was on a mission to make his message known to people of all ethnic groups. Taking the initiative by his own grace, he would go so far as to miraculously enable his witnesses to speak the languages of those groups rather than require them to learn the language of his people. This transcending of the language barrier is the defining miracle and symbol marking the launch of the church on God’s mission, and it is the defining theme of the book of Acts.

The stories of Peter at the home of Cornelius (Acts 10:23—48) and the "Jerusalem Council" (Acts 15:1-21) are exactly on the same point. Did God intend for Gentiles to become part of his own people, and if so, would they need to come under the Law of Moses, which had been the defining boundary of the Jewish people? By now we should realize that in Luke’s view, the only purposes of boundaries and fences were to climb on or jump over. And since the Jew-Gentile distinction was the most important boundary (ethnic, cultural, and theological) to Jews of that day, when it was relativized by the Jerusalem Council all other boundaries lost their absolute quality too. The one remaining definitive absolute was the Messiah, the Jewish Messiah who was and is the hope of all the nations.

What the existence of a multiethnic, multi-class church says to the world

Since boundary maintenance is a main preoccupation of all human groups, the existence of a boundary-transcending group is an anomaly. It will catch people by surprise, attract attention and demand an explanation. What is going on here? How is this possible? The explanation can only be Jesus, the Holy Spirit, and forgiveness, that is, the gospel. In other words, just by being itself as the Messiah-centered, multiethnic, multi-class community, the church raises the question to which the good news of Jesus is the answer.

This is what lies behind the phrase "You will be my witnesses" (Acts 1:8). The Messiah unites people of all classes and races in a way that no other force can. Their unity is a testimony to his power and presence. If there is a church of this united kind, there must be a Messiah, a defining center more important than any social dividing line.

HOW ARE WE RELATED TO JEWS?

It would have been easy and perhaps logical for Luke to present a gospel in which the Jewish features were neglected or even removed in order not to create problems for Gentiles who wanted to become Christians. As we have said, Luke was not Jewish himself. But what Luke actually did was stress the continuity between the Jews of the previous era and the multiethnic church of the new era (94.6).

For example, Luke does not describe the church as a "new Israel" (96.8). We are rather part of the old Israel, which has regrettably split down the middle over Jesus and his good news of God’s suspended vengeance (96.4). If we see Luke’s point, we can never let the church become a new Gentile group of privileged insiders who look down on the Jews as outsiders. To do so would be to fall back into the very error the Messiah came to remove!

Luke is therefore careful not to bash the Jews. His criticisms of the Pharisees are mild compared to Matthew’s blasts at them (92.5). His theology is so focused on Jerusalem that it looks like a Jew wrote it (93.6). In fact, "he has an exceptionally positive attitude to the Jewish people, their religion and their culture" (92.3). He goes to great lengths in chapters 1 and 2 to connect the birth of Jesus to Jewish prophecies about a Jewish messiah who would save Israel.

Here we come to the heart of the matter. For Luke, the Messiah is the hinge who connects the Gentile door to the Jewish doorframe. And this is the great offense for many Jews. They thought the arrival of the Messiah would be the day the filthy, oppressive Gentile door would be smashed and torched, not the day it would be salvaged and hinged to them! They would rather separate themselves from the Messiah than let the Messiah connect Gentiles to them.

HOW ARE WE RELATED TO JESUS?

Jesus had not been physically present on the earth for perhaps fifty years by the time Luke wrote. Very few still alive had ever seen Jesus. The connection of personal memory would soon be gone. What sort of connection would replace it? Only one of second-hand witness, written records and oral teaching?

Luke presents the Holy Spirit as our ever-present dynamic connection with the risen, ascended, and ruling Messiah. "The same Spirit in whose power Jesus went to Galilee also thrusts the disciples into mission. The Spirit becomes the catalyst, the guiding and driving force of mission" (113.8).

The Spirit is so central to mission that Jesus commands his followers not to begin their mission until he sends the Spirit on them. We might imagine they could have at least made a start on their own. After all, they knew Jesus' teaching and had seen his resurrection with their own eyes. They had plenty to teach and plenty to report. But Jesus forbade them to go anywhere until they were "clothed with power from on high"! (Luke 24:48).

This prohibition shows us how Jesus regarded his first batch of missionaries. Their mission was not primarily to spread his teaching or even to attest his resurrection. It was to do those things while showing the world that the same Holy Spirit who had descended on him at his baptism was living in them now.

In other words, Jesus himself was not really gone, nor was he present only in their memory. He was present by his Spirit. Matthew’s Great Commission had said, "J am with you always" (Matt. 28:20). Luke explains how that idea was and is fleshed out by the Spirit, incarnated in the believers. They are not merely human eyewitnesses; they were bearers of God’s mission, corroborated by God’s power. Hence Luke’s second volume is titled the "Acts" of the apostles, not the "Teaching" of the apostles or even the "Witness" of the apostles.

Since we have that ongoing connection with Christ, the "Great Commission" from Luke’s perspective is more a promise than a command (114.1). It is a description of what is bound to happen once the Spirit enters the disciples. They go on a mission not as "men who, being what they were, strove to obey the last orders of a beloved Master, but [as] men who, receiving a Spirit, were driven by that Spirit to act in accordance with the nature of that Spirit" (114.2, quoting Allen).

THE ONE REMAINING BOUNDARY

We might suppose that if all boundaries are transcended, all humanity is now included in God’s multiethnic, multi-class people and all are at peace with God. At last we can quit talking about God’s judgment and quit thinking in terms of "saved" and "lost." But such a view cuts the nerve of Luke’s idea of mission.

How can Luke, the boundary transcender, still insist on a strict boundary between repentant and unrepentant, forgiven and unforgiven, saved and lost? How can a writer so full of such mercy and grace also record so many instances of people who were not forgiven (such as the rich young ruler, Luke 18:23) and were even cursed with blindness (Elymas the sorcerer, Acts 13:8—11) or eaten up by parasites (Herod, Acts 12:21-23)?

This makes sense if we realize that the gospel of Jesus does not mean that all boundaries are gone. It means that only one boundary is left with any meaning — the boundary between those who "repent" (reorient themselves to face and welcome the Messiah) and the others. But the meaning of even this last boundary is different from the meaning of all other ethnic and class boundaries. Those inside the Messiah boundary are not to defend it but to cross it in mission. They are not to use the boundary to keep the outsiders out. Rather they are to go out across the boundary and bring in as many as they can (Luke 14:21-23).

"The Jesus Luke introduces to his readers is somebody who brings the outsider, the stranger, and the enemy home and gives him and her, to the chagrin of the 'righteous,' a place of honor at the banquet in the reign of God" (108.5). The so-called "righteous" are those who want to defend the boundary and let the outsiders get the judgment they deserve. Jesus wants to cross the boundary in grace and bring the outsiders in to a feast they do not deserve. Thus Jesus and the "righteous" are at cross-purposes, while Jesus and repentant sinners of all classes and nations (including Jews) are on their way to enjoying a meal together. Luke, the Gentile, will be at the table, loving every minute of it.

YOUR VIEWS AND YOUR CONTEXT

12. Suppose that Jesus' announcement of the good news was written this way in the New Testament: "The Spirit of the Lord is on me, and I have good news for everyone —rich or poor, powerful or oppressed, healthy or sick, Jew or Gentile, black or white." Would the gospel as you preach it fit better with that statement than with the real statement in Luke 4:18—19, which seems to favor the poor, the blind, and the oppressed? Discuss briefly.

13. Suppose you explain to a non-Christian friend Luke’s view of the church as a community that transcends social and ethnic divisions. The friend observes, "But the churches I know are divided along social and ethnic lines. How is this possible? Don’t they read Luke and Acts?" What would you say to that friend?

14. In the flow of the story of mission in Luke and Acts, what was the significance of the pouring out of the Holy Spirit on the church? How would the story have changed if this had not happened?

15. Compare and contrast Matthew’s model of mission with Luke’s. What

Chapter 4: Making the Most of the Grace Period

Paul’s Model of Mission

(Bosch, TM, pp. 123-78)

Paul, an apostle — sent not from men nor by man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father, who raised him from the dead —and all the brothers with me, To the churches in Galatia: Grace and peace to you from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ, who gave himself for our sins to rescue us from the present evil age, according to the will of our God and Father, to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen. (Gal. 1:1-5)

As we considered the mission texts of Matthew and Luke in light of the entire flow of their writings, so we will consider Paul’s views. Mission so permeates Paul’s thinking that it is hard to identify any parts of his writing that could not rightly be called "mission texts." [4]

The reasons are clear, Paul was a missionary —a person specially called and sent — from day one of his Christian experience (127.2), when his encounter with Jesus the Messiah on the road to Damascus caused the most dramatic U-turn ever made by a traveler (Acts 9:1-19). All his letters now in our Bibles were written either to churches that were mission outposts he pioneered or to individuals connected with his mission in some way. All his theology is "missionary theology" (124.7).

THE COSMIC GRACE PERIOD

[5]

If Matthew’s view of mission is disciple-centered and Luke’s is boundarycentered, Paul’s is time-centered. Paul is supremely conscious of the fact that through Jesus Christ, God the Father has inaugurated a cosmic grace period, a suspension of his judgment for a set time. (See "The Law of Moses" section beginning on p. 35.) Paul’s mission is to urge the nations to understand the meaning of this grace period and take advantage of it for the purpose God intended before it runs out.

Paul can readily understand and excitedly preach a cosmic grace period because he has experienced it in microcosm in his own life. He was an enemy of (be followers of Christ, but God by his own gracious choice intervened, turned Paul around, and gave him a new mission in life —to preach Jesus to the nations. "For Paul, then, the most elemental reason for proclaiming the gospel to all is not just his concern for the lost, nor is it primarily the sense of an obligation laid upon him, but rather a sense of privilege" (138.5, cf. Rom. 1:5, 15:5). Granted a personal grace period, he is overwhelmed with gratitude, which he expresses by spreading the news of the cosmic grace period (138.7). Given a divine calling, he calls others.

Let us look a bit closer at the concept of a grace period, a set time during which a debtor is not penalized for not paying a debt that has come due. The creditor unilaterally decides whether to give a grace period and if so, for how long. A debtor can do nothing to earn a grace period. At the end of the period, the debtor is required to pay the amount that was due at the beginning — no more, no less.

The cosmic grace period is similar in that God decided unilaterally to give humanity a grace period. The sins of our race came to a climax with the rejection and execution of Jesus, the central figure in God’s plan to establish his visible reign on earth. We humans should have had to pay for our crime right then, and pay with our lives, for we had taken a life in our murderous attempt to block God’s cosmic plan.

Instead of making us pay then and there, God gave humanity a grace period. He postponed the day of our judgment. This is good news, but Paul has even more to reveal. If we make proper use of the grace period, responding to it as our Creditor desires, we can have our debt canceled altogether. When the grace period ends, we will owe nothing! How is this possible? What is the secret to having our debt erased? Paul’s whole mission and his many explanations of the good news all answer this question, but none of the explanations will make sense unless we first understand that we are living in a period between the Messiah’s death and resurrection and the Messiah’s return. We must orient our lives to these two realities that mark the beginning and the end of the grace period.

THE LAW OF MOSES AND THE MESSIAH OF GOD

To understand why Paul is so struck by the grace period and so driven to explain his discovery to the whole world, we must realize how novel this concept was to someone schooled (as he probably was) in the Jewish apocalyptic tradition (140.1, 161.6). According to that tradition, God had set a time for executing judgment on the world using the standards of the Law of Moses, which defined the boundaries of God’s covenant people. On the appointed Judgment Day, God and his Messiah would strike the nations outside the covenant with sudden, overwhelming power and sweep them away, delivering his people from their oppression, idolatry, and wickedness forever.

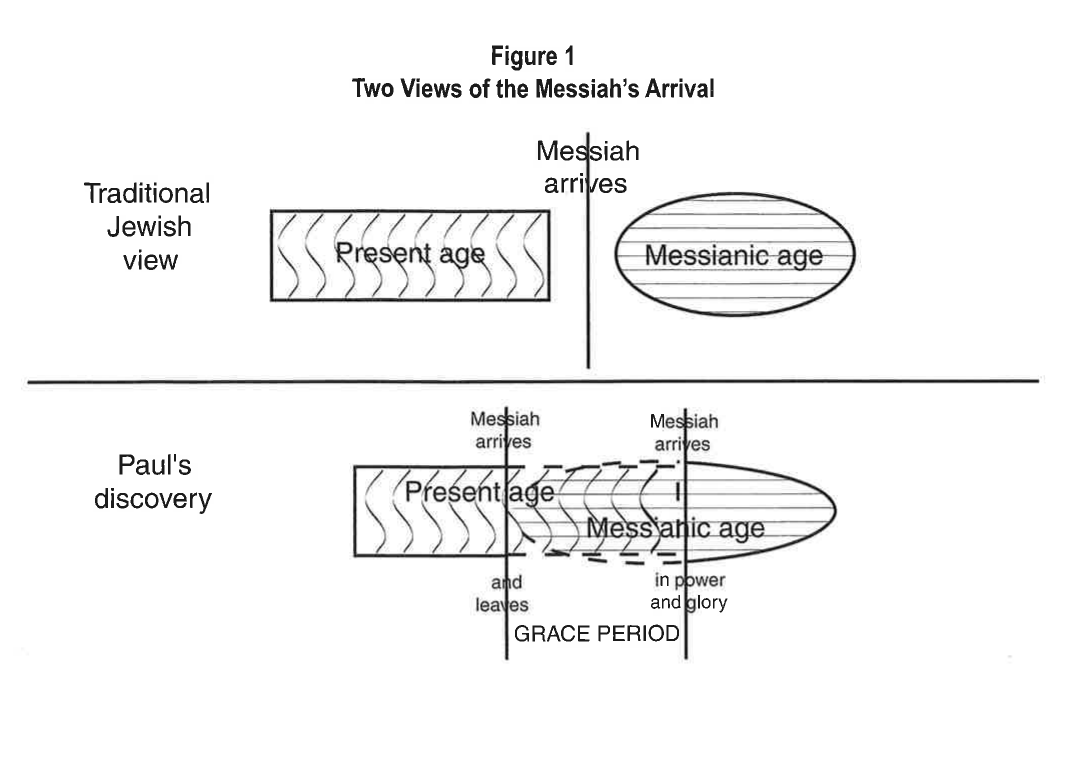

"Paul struggles with the problem that although the Messiah has come, his kingdom has not" (142.9). Instead of doing what the Jews expected, God has split the messianic arrival into two parts, inserting a completely unexpected grace period between them as shown in Figure 1 (p. 34).

The grace period changes everything. We are now living in two overlapping ages, as shown by the overlapping lines in Figure 1. The key to living in this time is to understand the new standard by which the world will be judged when the apocalypse finally does arrive as expected. Judgment will not depend on being inside or outside the Law but inside or outside the Messiah. As people used to be judged by how they responded to God’s gift of the Law, so now they will be judged by how they respond to God’s greater gift, the Messiah. If the Law of Moses was the ace of all religious systems, the Messiah’s arrival trumped it. That is why being "in Christ" (i.e., "in the Messiah") is such a common theme in Paul’s writings (e.g., Rom. 8:9, 12:5, 1 Cor. 15:22, Gal. 3:28, Phil. 1:1). Everything depends on it.

Of course, one must be sure that this Jesus whom Paul preaches is the real Messiah, and to do that, one must get around the very public fact that he died. Paul gets around it in two ways. First, he makes sense of the death by describing it not as the derailing of God’s plan but as the perfect sacrifice God uses to take the plan to a whole new level. "His substitutionary death on the cross, and that alone, has opened the way to reconciliation with God" (158.7, cf. 2 Cor. 5:18— 21). Second, Paul pins his entire life and message on the reports of Jesus' literal resurrection. "If only for this life we have hope in Christ, we are to be pitied more than all men" (1 Cor. 15:19).

MEGACHANGES

This central change from Law to Messiah brings other massive changes with it. Paul’s mission and his writings may be viewed as attempts to spell out these changes against the backdrop of Jewish apocalyptic thinking of his day

The distinction between insiders and outsiders

In Jewish apocalyptic there were clear-cut distinctions between light and darkness, good and evil, insiders and outsiders. If the standard of judgment on the Day of the Lord will be response to the crucified and risen Messiah rather than response to the Law of Moses, then the distinction between Jewish insiders and Gentile outsiders (which used to mean everything) means nothing at all any more.

Paul demands agreement about this, especially in Galatians. If people compromise on this point, they undo the meaning of their own baptism and compromise the core of the gospel itself (167.2). The same is true for differences of class and sex (Gal. 3:27). "In a very real sense mission, in Paul’s understanding, is saying to people from all backgrounds, "Welcome to the new community, in which all [whether former insiders or former outsiders] are members of one family and bound together by love' " (168.3).

The distinction between this age and the messianic age

Jewish apocalyptic maintained a black and white distinction between the current dismally corrupt, oppressive age and the glorious age that would begin with the Messiah’s arrival. Paul now sees that these ages overlap in the grace period between the two comings of the Messiah. Christians are those who recognize and welcome the Messiah today, thus putting one foot into the messianic age already. What will be true of the whole world in the messianic age is already partly true of Christians.

"The church is… the sign of the dawning of the new age in the midst of the old, and as such the vanguard of God’s new world. It is simultaneously acting as pledge of the sure hope of the world’s transformation at the time of God’s final triumph and straining itself in all its activities to prepare the world for its coming destiny" (169.8).

The relationship between God’s covenant people and the world

In Jewish apocalyptic, God’s people are under attack by evil forces of this world and therefore eagerly waiting to be rescued by the Messiah. The hostile world is a complete write-off from that perspective. But as Paul describes things, God’s people see that the grace period means there is real hope for the nations, even those who have oppressed God’s people until now. Instead of waiting for the nations to receive the blistering annihilation they so richly deserve, God’s people now have a mission to them, calling them to glorify God.

How will the church get the nations to listen? Mostly by being itself, that is, by being an exhibit of God’s new creation in Christ (168.7). As such, the church

wings the church is growing are its initiative toward the world and its response 'to the world’s persecution.

When taking the initiative, the church engages with the world in many ways, serving compassionately, treating people with the justice and peace that will be typical of life in the coming messianic age. God’s (eagle) people are " 'missionary by their very nature,' through their unity, mutual love, exemplary conduct, and radiant joy" (168.9).

The church recognizes clearly that these fine initiatives are out of step with the world’s "oppressive structures of the powers of sin and death. … As agitators for God’s coming reign; [God’s people] must erect, in the here and now and in the teeth of those structures, signs of God’s new world" (176.8). The world’s powers will certainly react and the church will certainly suffer but it will not respond to suffering as the Jews did. Instead, it will see suffering is "a mode of missionary involvement" in the world. God’s people on a mission are sharing in the suffering of Christ for the sake of the world’s redemption (177.6). The church is above all a sign of grace, and what clearer sign could there be than to accept suffering as Christ accepted it on the cross?

No apocalypticist had that outlook on either suffering or the world that inflicted it. They all wanted the Messiah to come, their own suffering to end, and the suffering of their persecutors to begin. Paul could no longer see the world in those terms.

Why all the changes could happen

The changes Paul describes are too radical and real to be brought about merely by a change of religious perspective or a new "law" brought by Jesus. They can only occur if some new spiritual power has become available, a power neither Jews nor Gentiles had ever had, a power no apocalypticist had dreamed possible for humans in the present age. According to Paul, this is exactly what has happened.

"For what the Jaw was powerless to do in that it was weakened by the sinful nature, God did by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful man to be a sin offering. … You, however, are controlled not by the sinful nature but by the Spirit, if the Spirit of God lives in you. And if anyone does not have the Spirit of Christ, he does not belong to Christ" (Rom. 8:3, 9).

The Law of Moses had pointed the way, but we humans could never get there. We always strayed or stumbled. The Spirit now picks us up, dusts us off, and carries us to the destination. To be "in Christ" (Paul’s favorite phrase) is to have this powerful, transforming Spirit within as part of us.

To be under the control of the Spirit of Christ is to be under the control of Christ himself. This is what it means to enter the "kingdom" (or control) of the Messiah. "For the kingdom of God is not a matter of eating and drinking

In other words, by the Spirit at work in the church, God is creating a new community made up of a new kind of human being so the world can have a sneak preview of life in the age to come. "If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has gone, the new has come!" (2 Cor. 5:17). "This evidence of the Spirit’s active presence guarantees for Paul that the messianic age had dawned" (144.2).

PAUL’S MISSION AND STYLE

This message of transformed apocalyptic is the message that Paul absolutely has to get out to the world at any cost. "He is charged with enlarging in this world the domain of God’s coming world" (150.8). He wants to make the most of God’s grace period, which means he wants others to make the most of it too. How does he go about this? Totally under the influence of the Spirit of Christ, that is, graciously, urgently, strategically, with the confidence of a man who knows he cannot lose.

1. Graciously

As the Messiah in his first coming to earth did not impose his rule on anyone, so Paul, his ambassador, does not badger anyone into putting faith in the Messiah. "Paul’s missionary message is not a negative one. … He does proclaim the wrath of God, but only as the dark foil of an eminently positive message — that God has already come to us in his Son and will come again in glory" (147.9). Paul reasons with people. He appeals. He pleads (2 Cor. 5:20). He graciously presents the message of grace.

This is Paul’s grace-filled message: "the proclamation of a new state of affairs that God has initiated in Christ, one that concerns the nations and all of creation and that climaxes in the celebration of God’s final glory" (148.3). But the new state of affairs does not come about automatically. "People have to 'transfer' from the old reality to the new by an act of belief and commitment" (149.1), that is, by the act of confessing that Jesus is Lord of all. "The taproot of Paul’s cosmic understanding of mission is a personal belief in Jesus Christ, crucified and risen, as Savior of the world" (178.5).

Those who trust Jesus as Messiah are "justified through faith" (Rom. 5:1), that is, already set right before God and adopted into the community that through the Spirit is gearing up for the messianic age. Their debt is canceled because they have renounced the human decision to crucify Jesus, which was what plunged the human race far deeper into debt than we had ever been.

To use a different image, it is as if these justified people have inhaled or absorbed the grace that God has injected into the world’s atmosphere through the

Paul is passionate but never belligerent about explaining this "inhale-thegrace" message. Jesus Christ makes so much sense to him that he believes many others who hear the good news will put their faith in Christ, as they have graciously been destined to do. All they need is a clear picture of God’s gracious plan, long kept secret but now revealed in Christ for the duration of the grace period.

2. Urgently

Paul’s mission is greatly affected by one decisive difference between ordinary grace periods and this God-given one — we, the debtors, have not been told how long the grace period will last. Though Paul does not go into much detail about what bad things will happen at the end of the grace period (148.7), he knows that when the grace period ends, grace ends. The mission is therefore urgent. Like soccer players in a game where regulation time has expired, we do not know exactly how much "injury time" the referee is adding on. Only the referee knows. When he blows his whistle, that’s it. No more goals can be scored.

This sense of urgency in mission is another sharp contrast between Paul’s writings and ordinary apocalyptic. Rather than looking forward (perhaps even with a sense of satisfaction) to the final whistle on the day when the Messiah will execute justice on the wicked, Paul wants to do all he can to reduce the number of wicked who will be punished on that day.

3. Strategically

Urgency calls for strategy, not frantic spurts of mission. Paul is strategic both at the theoretical and practical levels of mission.

On the theoretical level, God’s grace period is divided into two phases. In the first phase the good news of the Messiah whom the Jews rejected will be spread to the nations and they will welcome him as the Lord of all the earth. In the second phase the Jews, seeing the Gentiles flock to the Messiah, will become jealous of the way God is blessing the Gentiles. Then they themselves will turn to Jesus, the Messiah they rejected before the grace period started. Together Jews and Gentiles will enter a renewed world and cosmos under the Messiah’s reign.

This wildly creative plan of God is explained in the heart of Romans (chapters 9-11), which is the letter regarded as the heart of all Paul’s teaching. By no stretch of the imagination does Paul’s missionary strategy abandon the Jews. In fact, "It is Paul’s fundamental conviction that the destiny of all humankind will be decided by what happens to Israel" (159.7). Paul is concentrating on Gentile evangelization but still has the Jews in mind. He believes that success of the gospel among the Gentiles (phase 1) will create the conditions that will almost automatically bring on phase 2, Jewish conversion.

Ephesus], each of which stands for a whole region….In each of these he lays the foundations for a Christian community, clearly in the hope that, from these strategic centers, the gospel will be carried into the surrounding countryside and towns" before it is too late (130.2).

4. Confidently

Paul is dead sure of three things: the Messiah was here, the Messiah will be back, and in the meantime he is here among us by his Spirit. None of these depend on human design, human activity, or human timing. God has set things in motion and God is the timekeeper.

One thing God set in motion was Paul’s mission. As we noted in the quote at the beginning of this chapter, Paul was an apostle, "sent not from men nor by man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father" (Gal. 1:1). There is no stopping such a person. He and his colleagues are "afflicted — not crushed; perplexed — not despairing; persecuted — not forsaken; struck down — not destroyed" (177.6, see 2 Cor. 4:8f).

"Lesslie Newbigin suggests that nowhere in the New Testament is the essential character of the church’s mission set out more clearly than in the passage [referred to] above (2 Cor. 4:7-10). 'It ought to be seen," he says, 'as the classic definition of mission' " (145.4). Mission at its heart involves the conflict between the message of the messianic future and the forces of the anti-messianic present, the same "present" that put Jesus on the cross when the grace period began.

The world with all its might keeps trying to extinguish the witness of the messianic age, but those very efforts only enlarge and deepen the witness by showing the incredible resilience of the messengers. The world has not extinguished the witness but rather exhausted its own resources in the attempt. Now the only thing that can happen — must happen, will happen —is the collapse of the world and the triumph of God.

YOUR VIEWS AND YOUR CONTEXT

16. The analogy of the grace period is not in Bosch’s book. It has been added as an explanatory aid. What do you consider to be the strengths and weaknesses of this analogy?

17. Paul presents Jesus as being incredibly important because his life, death, and resurrection brought about a change from one historical period (the age of the Law of Moses) to the next (the cosmic grace period). However, many ethnic groups and religions do not attach much importance to the distinctions between any historical periods. Is Paul’s message then irrelevant to them? Is Jesus irrelevant? If not, how can the relevance be explained?

18. Agree or disagree with the following statement: The three changes from a Jewish apocalyptic worldview to a Christian worldview (insider—outsider, present age-messianic age, defensive-missionary) are so interwoven that if any one of them is true, the other two must also be true. Briefly explain your reasons.

19. Identify at least five themes mentioned in Galatians 1:1-5 and explain how they are woven together in Paul’s theology of mission.

20. Which of the four aspects of Paul’s style of mission (gracious, urgent, strategic, confident) do you think is least evident in the church as it goes about its mission in your country or region today? What problems does this cause? Write a paragraph that Paul might write on this subject if he came for a visit.

21. Based on the summary table of New Testament models of mission (Table 3, p.42), do you consider the mission perspective of Matthew, Luke, or Paul to be the most appropriate framework for mission in your context? What definition of mission are you using to evaluate their appropriateness?

22. In the bottom line of Table 3, which emphases shared by Matthew, Luke, and Paul are not shared by your church in a very noticeable way? To what extent do you share in the responsibility to do something about that discrepancy?

23. Write a prayer based on one or more of the ideas represented in the bottom half of Figure 1 (the Messiah’s arrival, p. 34).