Pastoral Theology, chapter 5

Margaret Whipp

- 29 minutes read - 6103 wordsChapter 5: The Fragility of Life; Attachment, Trauma and Loss

The joys of love and the pains of grief both touch the essence of what it means to be human. For pastors who are learning what it means to care, few things could be more important than to reckon with these two perennially mysterious aspects of human experience. In this chapter, we shall turn our thoughts to the tragic dimensions of human frailty and finitude, searching out what kind of theological resources might enable a ministry of healing. Our focus will be on the immensely tender encounters with suffering, grief and loss which cry out for pastoral kindness and wisdom.

Christian churches still offer, in a host of different ways, a ministry of pastoral care and support to countless individuals and families, particularly at times of loss. This ministry of prayer and presence is typically quiet, undemonstrative and easily taken for granted. Yet, it is notable that, despite a widespread loss of regular contact with religious teaching and practice, many people in our secularized society still turn instinctively to the Church to seek help and consolation at times of major tragedy and grief. Whether wistful half-believers or people of strong faith, those going through the deep waters of suffering and bereavement long for the comfort and reassurance of a hope that is anchored in God.

This chapter will introduce some of the essential foundations for a faithful Christian ministry to the suffering, dying and the bereaved, tracing the landscape of loss in all its exquisite sensitivity and sketching a tentative pastoral vision for compassionate care and support.

Frailty and finitude

Part of life’s mystery is its terrible fragility. Despite our best human efforts to protect ourselves and those we love, the changes and chances of earthly life promise no lasting stability and no certainty or assurance that any of us will be immune from affliction. Religious wisdom teaches, on the contrary, that all human life is vulnerable to sorrow and sadness and that true faith is not a matter of denying fragility, but rather of seeking the resources to grow through it.

The scriptures often picture human vulnerability before God in terms of the ultimate dependence of a child. Frail children of dust, and feeble as frail, in Thee do we trust, nor find Thee to fail', as the familiar hymn renders the psalmist’s cry (Ps. 104.27-30). This is not to indulge an infantilized response to common human frailty, but to promote a realistic and trustful sense of dependence on God.

It is easy to lose sight of this ineluctable vulnerability in a culture which has become fixated with the avoidance of risk. Modern Western societies, with all the benefits of insurance, social security and generous health provision, do their level best to cushion individuals from the existential impact of frailty and finitude — until tragedy comes finally and fearfully close to home. At such times, the shock of facing up to the realities of human affliction is then all the harder to bear.

As a father has compassion on his children, so is the Lord merciful towards those who fear him. For he knows of what we are made; he remembers that we are but dust. Our days are but as grass; we flourish as a flower of the field; For as soon as the wind blows over it, it is gone, and its place shall know it no more. But the merciful goodness of the Lord is from of old and endures for ever on those who fear him, and his righteousness on children’s children.

— Psalm 103.13-17

Historians and social anthropologists describe stark contrasts in modern attitudes to death in comparison to our forebears. The demography of bereavement has changed beyond recognition in recent centuries. From the days when death could strike at random in any village or any family, making the experience of bereavement utterly commonplace and natural, modern societies with less routine experience of the intrusion of tragedy have fostered an illusion that death can somehow be kept under control, or for the most part held at bay.

One worrying result of changing life expectancy is that the encounter with death has become unfamiliar and remote, so that our shared cultural resources for responding to itare correspondingly less secure, Whereas an earlier Christian culture sought to enfold its members in an art of dying (ars moriendi) as much as in a shared understanding of living, the ways of approaching death and bereavement in our post-modern society have now fragmented to become a matter of personal choice. The ongoing debate about legalization of assisted dying is one very telling example of this breakdown of shared social values.

In such acontext, Christian pastors need to reflect deeply on the rich resources of our theological and liturgical traditions, considering how best to make these available to those who may seek our care. It will be beyond the scope of this book to explore in detail the range of ministries appropriate to prayerful healing or the enormous contribution of Christian funeral ministry; but the broad principles of theological, psychological and pastoral responses to suffering and loss are laid out in this chapter so as to provide an essential orientation for any pastoral worker who is beginning to make a contribution in this area.

An unfailing covenant

For people of faith it is clear that neither the protection afforded by socioi- economic security, nor the promise of ever-improving medical technology, can finally assuage our primitive existential fear of mortality. Although we should rejoice that many of the fearsome causes of death and dependence can be deferred through the blessings of modern health and social care, we must also recognize that frailty and finitude continue as inalienable aspects of human nature which cry out for deeper, spiritual resources of wisdom and care.

We have seen in Chapter 2 (Being Human) that a Christian vision of life in all its fullness is one which is not diminished by the realities of suffering and death. On the contrary, a theological anthropology which images human beings in relationship with the eternal life and love of the Trinity directs us towards an unfailing spring of hope and consolation in the face of heartbreak and loss.

We can find many entry points within the scriptures for pastoral reflection on suffering and loss. Traditionally Christians have often turned to the Hebrew psalms with their poignant evocations of the many shades of human experience. The psalms show us how to give voice to lament, uttering deep outpourings of anguish and questioning alongside heartfelt shouts of thanksgiving and praise. This powerful tension between dreadful anguish and fervent faith is held together within a typically forthright expression of soulful prayer.

How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me? How long must I bear pain in my soul, and have sorrow in my heart all day long? How long shall my enemy be exalted over me? … But I trusted in your steadfast love; my heart shall rejoice in your salvation. I will sing to the Lord, because he has dealt bountifully with me.

— Psalms 13.1-2, 5-6

In a different genre, the prophetic writers also plumb the depths of human distress as they grapple theologically with the appalling disorientation visited upon the people through political catastrophes, humiliation and exile. Again and again, the prophets return to the theme of God’s faithful covenant and the unbreakable bond of care which God has established with the people who are called by his name.

But Zion said, "The Lord has forsaken me, my Lord has forgotten me." Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you. See, I have inscribed you on the palms of my hands.

— Isaiah 49.14-16

Christians read these powerful testimonies from the Hebrew scriptures through the lens of Jesus' own cross and resurrection and the promise of inexhaustible comfort which he bequeaths to the Church.

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of all mercies and the God of all consolation, who consoles us in all our affliction, so that we are able to console those who are in any affliction with the consolation with which we ourselves are consoled by God.

— 2 Corinthians 1.3-4

However, it would be foolish to imagine that we can nail down any text or trite theological formulation, Christian or otherwise, which pastors can turn to in order to neatly 'answer' the searing questions posed by human suffering. What the scriptures point towards, and what saints throughout the generations have borne witness to, is a powerful experience of the mysterious, unbreakable bond of God’s loving faithfulness, which richly sustains the agonized soul. And because this bond has been sealed in the deepest and costliest sacrifice, through the shedding of Christ’s own blood, there is no human loss, no crisis, no trial or tribulation which can ever exhaust his promise.

For I am convinced that neither death nor life, … nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

— Romans 8.38-39]

Attachment and security

An abiding sense of deep and unbreakable bonds of attachment is one of the most precious anchors for any human being in times of trouble. Modern psychological understandings of the emotional significance of personal 'attachment' provide many fruitful insights for a contemporary understanding of the dynamics of suffering and loss. In the light of this theoretical resource, Christian thinkers are increasingly reflecting on the concept of 'attachment' as a richly suggestive model for thinking about the pastoral dimensions of our human relationship with God. [1]

Current thinking about attachment theory has its roots in comparisons between animal behaviour research (ethology) and psychoanalytic studies of children. In the framework developed by John 'Bowlby, the concept of 'attachment' is used to describe a close affectional bond typically developing between a young infant and her parent. Bowlby recognized that a secure sense of attachment at a young age is fostered by warmth and affection, sensitivity, responsiveness and constancy, and that children who are deprived of these foundational experiences of parental attachment may struggle to develop trusting intimate relationships in future life.

The characteristics of a good attachment relationship were outlined by Mary Ainsworth’s studies of parenting behaviour.

Safe haven — when the child feels threatened or afraid, she can return to the caregiver for comfort and protection.

Secure base — the caregiver offers a secure and dependable base from which to go out confidently and explore the world.

Proximity maintenance — the child strives to stay close to the caregiver, whom she trusts will keep her from harm.

Separation distress — when separated from the caregiver, the child will express anxiety and distress.

Building on these original insights, a wealth of psychological theory and application has unfolded as th edynamics of attachement behaviour have been closely examined at every stage of life. From the earliest stages of elemental trust described by Erikson through to the devastating trauma of grief when intense bonds of relationship are severed, attachment theory can illuminate the way in which close ties of durable human commitment are foundational for emotional security and well-being.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that similar patterns of trust, dependence and constancy can be discerned in the way that believers try to describe a personal relationship with God. Although it can be misleading to press the analogies too far, there are profound connections to be drawn between the experiences of human intimacy and the security that comes from a trustful relationship with God. Since human language about God and our ways of conceiving his presence can only be expressed in terms we can understand, it is entirely natural that we should think and speak of loving and nurturing relationships as a kind of spiritual attachment to an infinitely caring God. It is from such deep wells of consoling spirituality that pastors learn to draw their resources as they come alongside people in suffering.

God isa safe haven: When I am afraid, I put my trust in you (Ps. 56.3).

God is a secure base: You are indeed my rock and my fortress; for your name’s sake lead me and guide me (Ps. 31,3).

Proximity maintenance is a spiritual necessity: Your face, Lord, do I seek. Do not hide your face from me (Ps. 27.8-9).

Separation distress drives the yearning soul back to God:r Do not forsake me, O Lord; O my God, do not be far from me; make haste to help me, O Lord, my salvation (Ps. 38.21-22).

Establishing and sustaining a strong relationship of attachment to God can be seen in this light as one of the focal priorities for Christian maturity. In the remainder of this chapter we shall explore how this priority might be addressed in situations of crisis, and specifically in ministry to the sick, the dying and the bereaved.

Crisis and disorientation

How are we to imagine a faithful Christian response to sorrow and grief, when the most vital attachments of earthly life are mortally threatened? We began to sketch out in Chapter 3 (Faithful Change) how the crises of life, whether developmental or situational, furnish both challenges and opportunities for a deeper spiritual maturity. Such crises can be particularly acute at times of loss when all the familiar landmarks of emotional security are grievously disturbed.

Of course, the crisis of bereavement is not the only kind of painful upheaval to assail the human spirit. Profound disorientation can result from any major life event - the loss of a job, break up of a marriage, a financial crisis, an accident orillness, an unwanted pregnancy, a major move of home or occupation, a local or national disaster, the challenge of caring for elderly parents, the birth of a disabled child. In any of these situational crises, the whole architecture of emotional and spiritual security can be shaken to the core as the taken-for-granted landscape of familiar attachments is drastically unsettled.

To generalize about the experience of loss, however, can be patronizing at best and, at worst, cruelly off target. It is sadly neither true nor helpful to say to anyone, 'I know how you feel' If we draw any wisdom from scientific theories of the common human experience of grief, we would be wiser still to remember that loss is so exquisitely painful largely because it is so uniquely individual. There are nevertheless sufficient basic commonalities in the broad movements of loss and readaptation which, sensitively considered, can help to inform a tentative pastoral response.

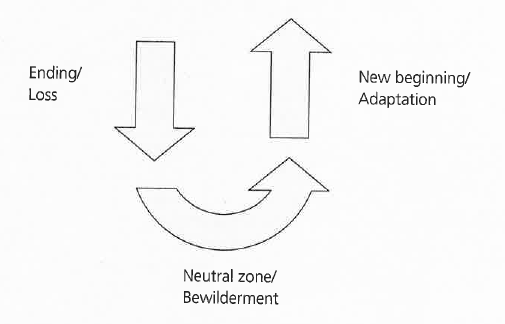

The simple U curve of transition which was introduced in Chapter 3 is a helpful reminder of the depth of dissonance and disorientation which accompanies grief. Whether long drawn out, or desperately acute, the experience of plunging down into a deep valley of anxious bewilderment is something which most of us recognize only too well. It is into this territory that the pastor brings a Christian presence. The first prerequisite in ministering to someone in the depths of anguish is presence. It is not to offer a sophisticated theoretical explanation of their situation, but simply and genuinely to show that you care. How that care is expressed in practice may be an awkward combination of the love of the amateur and the discernment of the professional. But the humble pastor strives to bring a professional steadiness in the midst of crisis together with all the tender-heartedness of the sincere friend, aware that in the midst of sorrow she too is a frail earthen vessel whose strength and consolation comes only from God (2 Cor.4.7).

It is the rock-like character of that strength and consolation, founded on God, which can be a vital gift to share ina crisis. While many people show enormous resilience in the face of suffering and loss, there are times of overwhelming distress in the lives of many individuals and families when the need for an upholding presence is acute and raw. At such times, the steady objectivity as well as the loving sensitivity of the minister will be crucial.

## Pastoral Story

Martin, the 24-year-old son of a somewhat disaffected church family, was tragically killed in a climbing accident. Several of his friends had shared connections with the church as boys — through the church school and scouts group or as bell ringers. His fiancée lived 70 miles away. His parents and younger brother and sister suffered intense shock.

The vicar’s first contact with Martin’s parents was delicate, but purposeful. He established clear and open communication with the family and made prompt arrangements for the timing of the funeral. He briefed key members of the pastoral team and paid a visit to the pub and the local school, where Martin was still fondly remembered. Prayers were said in church every day, and several local friends called in to light candles. The vicar made time for visits as well as phone calls and emails, as details of the funeral began to take shape. There were many moments of deep, tender silence, as the dreadful shock was held and shared. And there were gentle smiles, as well as tears, as bitter-sweet stories from Martin’s childhood were passed around members of the gathered family. The funeral was a memorable occasion, with a fabulous peal of bells as Martin’s coffin was taken out of church. A year later, when Martin’s former fiancée visited the church on the anniversary of his death, she called to thank the vicar for the care that the church had shown. She had never realized how much the support of a Christian community could mean and was now attending a church in her own area, where she hoped to be confirmed.

A simple model of practical crisis intervention can be adapted for pastors who are drawn in to help people at times of overwhelming distress. Switzer and Stone offer an outline of the 'ABC' of pastoral crisis counselling which goes some way to shaping the generic dynamics of effective crisis support. [2]

A-— Achieve contact. When people are deeply shocked or troubled, the initial approach is a sensitive matter. The arrival of a church minister, with or without a dog collar, may not be an immediate source of reassurance to some people; and care must be taken to achieve and to build rapport. The skills of attentive listening are essential, offering a full and undivided attention together with deep and generous empathy.

B — Boil down the problem to its essentials. It is easy to be ineffective in a crisis, when the intensity of feelings tumble out in infantile distress, or threaten to paralyze otherwise normally competent adults. The pastor, similarly, may feel deeply unsettled by a shocking situation and find it hard to focus on what can be done to help. It takes a cool head and a warm heart to attend deeply to the issues at hand, offering sufficient meaningful response — whether emotional, spiritual or utterly practical — to ease the burden of immediate distress and bring the assurance of ongoing support.

C — Cope actively with the situation. The beginnings of a turn towards adaptation lie in the ability to look purposefully towards the future. Beyond mere sympathy, the sensitive pastor can help to facilitate an intentional response toa crisis by helping people to mobilize their spiritual, emotional and practical resources for the next steps that must be taken.

It is wise to recognize that this kind of ministry at times of acute strain, although potentially a source of rich fulfilment, will be also inevitably draining. The humble minister knows that her effectiveness for others depends more than anything else on the security of her own spiritual attachment to God. It is only as she goes on learning to plumb the depths of her own buman vulnerability that she will develop sufficient spiritual poise and self-awareness to venture a holding and healing ministry to other troubled souls.

Healing and wholeness

Historically, the Church has always offered a rich and diverse range of ministries of healing and wholeness.' [3] From the ancient traditions of care and hospitality undertaken by monastic communities, to more recent professional developments in fields such as hospital chaplaincy, Christians have ministered to the sick through prayer and sacrament, counsel and practical care, bringing the felt presence of covenantal love into the lives of suffering people through compassionate action and, above all, pastoral presence.

It is not immediately obvious, however, how best to relate a contemporary ministry of spiritual healing to the dominant biomedical paradigms of physical treatment and cure. Popular misunderstandings of Christian healing abound. 'At one extreme is the naive supernaturalism which embraces uncritical theologies of miraculous healing in an attempt to compete with secular treatments through a show of triumphalist and charismatic power. At the other extreme is the theologically vacuous pursuit of the kind of pseudo-professionalism which tries to 'baptize' secular techniques, for example in psychotherapeutic counselling, by giving them a veneer of spiritual respectability without any attempt to grapple theologically with their underlying anthropological presuppositions.

It is beyond the scope of this book to critique these distortions in rigorous detail. More constructively, we might consider how a theological understanding of life in all its fullness might provide a touchstone of integrity by which to evaluate our pastoral practice in this area. (See Chapter 2 for a full discussion of theological anthropology.) This perspective will help us in shaping @ properly Christian approach to healing and wholeness amid the realities of life in all its times and seasons, life in all its frustration and fragility, life in all its mutuality and communion and life in all its hope and potential.

On this account of human wholeness, we can begin to imagine how ministries of spiritual healing work to address the brokenness which is in some way out of step with life’s times and seasons; unable to integrate life’s frustration and fragility; alienated from life’s mutuality and communion or incapable of embracing life’s hope and potential. Whether it is through the simplest ministry of visiting the lonely or in the most sensitive ministries of pastoral counselling and reconciliation, the aim of any authentically Christian work of healing and wholeness will be to deepen and renew the kind of attachment to God through which the faith and hope and love of human beings made in God’s image begins to be restored.

These principles are of the utmost importance when sharing a ministry of healing and wholeness with the dying and bereaved.

Walking the valley

The manifold skills and sensitivities of pastoral care — theological and ethical, personal and sacramental — are rarely so richly engaged as in the ministry of journeying alongside people towards their death. In the history of Christian pastoral care, the Church has regarded ministry to the dying as one of its highest priorities. Today, in our seemingly more secular age, the influence of the hospice and palliative care movement has brought renewed emphasis to the importance of spiritual ministry for those approaching death.

Cicely Saunders coined the memorable phrase 'total pain' to indicate the holistic challenge of easing suffering at the end of life, when physical pain may be only one aspect of a much broader anguish relating to multifaceted social, emotional and spiritual concerns. Although the latter dimensions may be less amenable to clear-cut description or diagnosis, there is a growing body of research which informs a pastoral understanding of spiritual 'pain. Whether practising believers or not, human beings in the face of death have a need for hope, meaning and forgiveness — both in relation to the past and present and also in light of a dimly imagined future.

It is a remarkable privilege to be invited to walk alongside a person in the valley of the shadow of death — to learn from them, since none of us has walked that road ahead of others, and to offer whatever small gestures of care may bring sustenance for their journey. In this final pilgrimage of wholeness and healing, the role for a Christian minister may be considered under seven headings.

Companion

Dying is a uniquely lonely affair; and the path that leads away from all familiar and comforting relationships is hard for mortal human beings to tread. The minister’s personal visit is therefore one of the most meaningful acts of pastoral presence. It is also the most profoundly human response of basic companionship. (The word co mpanionship reminds us etymologically that as fellow mortals we share the same bread, and as fellow Christians we feast on the same bread of heaven.) Whether or not the pastor brings the sacramental gift of eucharistic ministry it is her simple presence — being there — with a willingness to share something of the instinctive dread of the abyss, which provides hope and en couragement that the dying person is not left to face the darkness alone.

Carer

The most basic elements of care — giving time, offering touch, with deep and generous attentiveness — take on a heightened significance when life itself is ebbing away. The personal presence of the pastor, face to face with the dying soul, speaks of the unfailing covenant of God’s care. And because of the representative nature of her role, each small gesture of care can enrich and sustain the bonds of attachment to an eternal and undying love.

Comforter

From the original meaning of the word, this aspect of ministry is more about giving strength than offering consolation. Dying is hard work: and the dying soul needs spiritual resources that will sustain her on the journey. The simplest words and symbols can bring enormous comfort, but only if they are accessible

to the person concerned. This is not the time for extended philosophical debate, put for basic crumbs of comfort which are meaningful and sustaining to the pungry spirit. The sensitive pastor will take her cue from careful listening and prayerful discernment. Surprisingly often the most elementary liturgical fragments—a remembrance of childhood hymns, the familiar phrases of the Lord’s Prayer, the simple touch of prayerful anointing — will re-engage @ primordial attachment to the deepest roots of faith.

Confessor

Making peace with the past is often the prerequisite to finding peace in the arms of God. For those schooled in the practice of a Catholic faith, the gift of formal absolution by a priest can bring immense healing as death approaches. For Christians of other traditions, as well as for many more who do not think of themselves as religious, the opportunity to unburden themselves in the presence of someone who represents the reconciling ministry of the Church can bring unexpected relief, with a sense of grateful acceptance that some of life’s 'unfinished business' can finally be laid aside.

Counsellor

Facing up to the past can release fresh energies to grapple with the awesome challenges of the present. The pastor as counsellor offers her best skills of prayerful listening in the kairos time of final struggles, evaluations and decisions, when the last acts and intentions of a life that has run its course present a richly rewarding opportunity for gratitude, blessing and release.

Commender

[At the bedside of a dying person, the Christian minister treads on holy ground. 'As the concerns of life’s past and present give way to beckoning intimations of eternity, her prayerful presence holds open the door that stands between earth and heaven. Using time-honoured words of commendation, or rough-hewn prayers of the heart; alone, or in company with supporting family and friends; aloud, or in the silence of a watchful spirit; it is her privilege to commend to God’s love and mercy the soul who sets forth on her final journey home.

Contemplative

Who is sufficient for these things?

— 2 Corinthians 2.16

No matter how sophisticated her theology or how well-honed her counselling skills, every honest minister will tremble with inadequacy before the ultimate mysteries of death and eternity. In her ministry to the dying, the humble pastor can be almost unbearably exposed to doubt, hollowness and confusion, It is therefore only in stillness, prayer and naked trust in God that the contemplative minister will be replenished with deep wells of quiet courage for this awesome, but astonishingly beautiful ministry of love.

Picking up the pieces

## A prayer for those who mourn

O God who brought us to birth, and in whose arms we die: in our grief and shock contain and comfort us; embrace us with your love, give us hope jn our confusion, and grace to let go into new life, through Jesus Christ. Amen.

— Janet Morley [4]

Approaches to healing and wholeness in pastoral care of the bereaved have been informed by a vast amount of research into the complex and overwhelming processes of human grief. Tidy-minded theorists sometimes imagine that the confusing experiences of grief can be systematized into a simple framework of memorable psychological phases. By analogy with the predictable stages by which physical wounds heal, for example, Colin Murray Parkes in 1972 used attachment theory to construct an orderly sequence of responses through which the emotional wounds of grief could be envisaged to 'heal' over the course of months and years.

His widely known model, along with the descriptions of other bereavement experts, sheds some helpful light on the dark inner landscape of grief — the initial numbness and denial; the yearning and raw loneliness that is often physically as well as spiritually painful; the disorganization and despair of a life that has lost its bearings; and the eventual quiet movement towards acceptance, readaptation and new purpose in living. Finding a language to describe the sometimes alarming symptoms of acute and persistent grief can be a useful tool to foster empathy with those who mourn, helping them to know that they are not alone in their distress. [5]

Yet, sensitive pastors recognize that no tidy structure is likely to do justice to the inherently chaotic experience of grief, in which the whole orientation of both inner and outer worlds may be painfully disrupted. The best that theoretical models of bereavement can offer is to augment the limited experience and understanding of carers; but it is a mistake to imagine that scientific tools alone will provide a shortcut to deep listening, searching faith and costly, personal care. In the final part of this chapter, we shall turn therefore to the wider pastoral question of how the whole Christian community is called to share in the profoundly hope-fulll task of 'picking up the pieces' of loss.

## Pastoral Story

Beverley was a middle-aged African-Caribbean woman whose huspand, Joe, died suddenly of a heart attack. Although she had no previous links with her local church, she appreciated the kindness shown to her at her husband’s funeral and started to attend the Sunday morning services from time to time.

About six months after the funeral, Beverley broke down in tears at the end of a service. She told Sheila, one of the welcoming team, that it would have been Joe’s birthday that week. She felt terribly lonely and was struggling to go on with life without him.

Sheila was able to invite Beverley to her thome for lunch on the day of Joe’s birthday. They talked together about all kinds of memories, and Beverley said that she wanted to light a birthday candle for Joe in the church. Later jn the day they went together to the church. Beverley lit a candle, and the pastoral worker offered a simple prayer of healing, thankfulness and peace.

Through tears and laughter, lighting up his birthday candle against the darkness of grief, Sheila joined with Beverley in a profoundly pastoral act of solidarity to sing 'Happy Birthday' one last time for her Joe.

Christians believe in a love that conquers death. This faith is not an abstract doctrine about an unimaginable future destiny, but a solid conviction about the healing power of undying love which binds all God’s people together in hope. This deep conviction expresses itself just as much in practical gestures of compassion as in sensitive theological reflection. It is not the sole preserve of ordained ministers, but is a natural part of the witness of the whole Church.

Informal befriending and social networks;

Bereavement groups and courses;

Pastoral visiting schemes;

Regular prayers to remember the dead;

Bereavement services, especially at All Souls' in November.

All these humble gestures of pastoral care testify to the solidarity in suffering and hope that is the Christian’s enduring legacy. 'The end is gain, of course; wrote Marjorie Allingham in the light of her own grief. 'Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be made strong, in fact. But the process is like all human births, painful and long and dangerous. [6]

Being human, being there, being good news

There are many specialist ministries of pastoral care and counselling which some priests and ministers are trained to offer for work with the sick and suffering, the dying and bereaved. It is not the purpose of this book to survey in any detail the knowledge’and competencies which are required of those who provide a professional level of care, in the context of appropriate referral, for people with complex physical or mental health concerns, people struggling with complicated grief, or people seeking the grace of sacramental confession. No pastor should expect to work beyond her limits.

This chapter has sought to orientate the humble pastor with sufficient compassionate wisdom for a demanding, yet remarkably fulfilling, area of pastoral care. In the face of sadness, crisis and grief, the core elements of Christian pastoral care remain terribly simple: being human, being there and being good news.

Questions

'Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I fear no evil; for you are with me; your rod and your staff — they comfort me. (Ps. 23.4)

Further Reading

Ainsworth-Smith, Ian and Peter Speck, 1982, Letting Go: Caring for the Dying and Bereaved, London: SPCK.

Billings, Alan, 2002, Dying and Grieving: A Guide to Pastoral Ministry, London: SPCK.

Bowlby, Richard, 2004, Fifty Years of Attachment Theory, London: Karnac Books,

Brueggemann, Walter, 1984, The Message of the Psalms, Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press.

Cassidy, Sheila, 1988, Sharing the Darkness: The Spirituality of Caring, London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

Cobb, Mark, 2001, The Dying Soul: Spiritual Care at the End of Life, Buckingham: Open University Press.

Evans, Abigail R., 2011, Is God Still at the Bedside? The Medical, Ethical, and Pastoral Issues of Death and Dying, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Kelly, Ewan, 2008, Meaningful Funerals: Meeting the Theological and Pastoral Challenge ina Postmodern Era, London: Mowbray.

Ktibler-Ross, Elisabeth and David Kessler, 2005, On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss, London: Simon and Schuster.

Lewis, C. S., 1961, A Grief 'Observed, New York: Harper and Row.

Nouwen, Henri J. M., 1982, A Letter of Consolation, San Francisco: HarperCollins.

Parkes, Colin Murray, 2006, The Roots of Grief and its Complications, London: Routledge.

Stump, Eleonore, 2012, Wandering in Darkness: Narrative and the Problem of Suffering, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swinton, John, 2007, Raging with Compassion: Pastoral Responses to the Problem of Evil, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Switzer, David, 2000, Pastoral Care Emergencies, St Louis, MS: Baker Academic.

Whitaker, Agnes (ed.), 1989, Allin the End is Harvest, London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

Wolterstorff, Nicholas, 1987, Lament. for a Son, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Woodward, James, 2005, Befriending Death, London: SPCK.